Reports

An overview of new data on the relative effectiveness of flu vaccines in vulnerable populations

This report is based on medical evidence presented at sanctioned medical congress, from peer reviewed literature or opinion provided by a qualified healthcare practitioner. The consumption of the information contained within this report is intended for qualified Canadian healthcare practitioners only.

MEDI-NEWS - Influenza Vaccine Effectiveness in Seniors and Other High-risk Groups

September 2020

As healthcare professionals prepare for flu season in a pandemic year, the results of three large, population-based U.S. studies now provide comparisons of the relative effectiveness (rVE) of the available flu vaccine formulations in high-risk patients. In a study published in August 2020, a vast retrospective cohort analysis of almost 2 million U.S. patients over 65 years old compared adjuvanted to non-adjuvanted flu vaccine. In September, 2020, a prospective study in 823 U.S. nursing homes provided a similar comparison in more than 50,000 patients. Also last month, a retrospective cohort analysis of over 3 million U.S. patients yielded rVE data for egg-based versus cell-based vaccines in high-risk patients aged 4–64. The goal of this literature alert is to provide an overview of these new studies to Canadian healthcare professionals preparing for this year’s flu season.

Chief Medical Editor: Dr. Léna Coïc, Montréal, Quebec

The SARS-CoV-2 pandemic has highlighted to a wider audience the vulnerability of older people to respiratory disease, especially those in long-term care. In Canada, 80 percent of COVID-19 deaths have been in nursing homes, prompting calls in the Canadian Medical Association Journal (CMAJ), and elsewhere, for changes in public policy.1,2

Similar concerns have always applied to influenza. During Canada’s 2017–2018 flu season, 76 percent of flu-related hospitalizations were in seniors, according to Dr. Melissa Andrew, associate professor of geriatric medicine at Dalhousie University, speaking at last year’s conference of the International Society for Influenza and Other Respiratory Virus Disease (ISIRV). In the 2019–2020 flu season in the U.S., the over-65s accounted for 62 percent of deaths and 43 percent of hospitalizations.3

Infection-control challenges in crowded nursing homes undoubtedly favour the virus; in addition, vaccine effectiveness itself declines with frailty (rather than age per se), said Dr. Andrew, due to immunosenescence and comorbidities. To increase vaccine effectiveness, the current options are to increase the dose or add an adjuvant, Dr. Andrew concluded.

In Canada, high-dose trivalent (HD-TIV; Fluzone) and adjuvanted trivalent (aTIV; Fluad) influenza vaccines are both approved for use, although availability varies across the country. For patients over 65 years old, Canada’s National Advisory Committee for Immunization (NACI) takes a pragmatic view: its guidelines for the 2020–2021 flu season recommend that HD-TIV “should be used over [low-dose TIV]”, but any vaccine can be used, based on availability.4 Canadian guidelines avoid specific recommendations on whether to vaccinate seniors with a HD-TIV versus aTIV.4

New Data on Relative Effectiveness of

Flu Vaccines in the Elderly

A timely paper by Dr. Kevin McConeghy (PharmD) of the U.S. Veterans Administration (V.A.) and colleagues from Brown University, Providence, RI, compared adjuvanted to non-adjuvanted TIV in U.S. nursing homes.5 Published in Clinical Infectious Diseases on September 4, 2020, the cluster-randomized study of 823 facilities was the first prospective trial of an adjuvanted vaccine in a long-term care setting.

During the 2016–2017 flu season, McConeghy’s team randomized 50,012 nursing-home residents aged over 65 to be offered either TIV or aTIV. Outcomes were tracked using Medicare claims compiled independently by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), an arm of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The primary outcomes were “respiratory-related” and “all-cause” hospitalization rates; secondary outcomes included “hospitalization with a primary diagnosis of pneumonia or influenza” (P&I) and all-cause mortality. The study was funded by Seqirus.

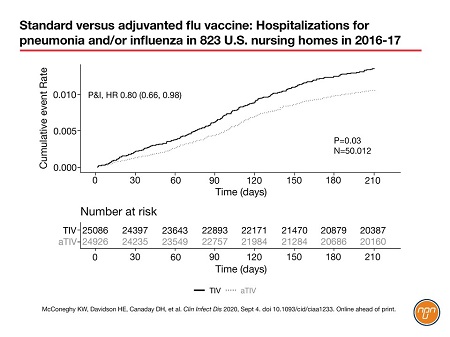

More than 80 percent of the residents decided to be vaccinated. The researchers found that the adjuvanted vaccine was associated with a significant 6% reduction in all-cause hospitalization (HR 0.94; P=0.02; covariate adjusted) and a 21% reduction in hospitalization for P&I (HR 0.80; P=0.03; covariate adjusted; Figure 1). Hospitalizations for ‘respiratory-related’ disease were similar for the two vaccines.5 The authors speculated that this apparently contradictory result could be due to the wider variety of diagnoses that lead to a “respiratory-related” code being input to the CMS system (code ICD-10 J). By contrast, the code for “pneumonia or influenza” might have had “a greater specificity for an influenza vaccine-associated outcome,” said the authors.

Figure 1. Standard versus adjuvanted flu vaccine: Hospitalizations for pneumonia and/or influenza in 823 U.S. nursing homes in 2016-17

The 2016–2017 season, during which the McConeghy nursing-home study took place, was notable for its low overall vaccine effectiveness in the over-65s: 20 percent overall and 21 percent against A/H3N2, the predominant circulating influenza strain that season.6 The authors noted that the well-documented effectiveness of aTIV against A/H3N2 could have favoured the adjuvanted vaccine in their study.

Commenting on the McConeghy study, Canadian infectious disease specialist Dr. Mark Loeb of McMaster University observed that having two primary outcomes was unusual. Aside from that, Dr. Loeb said the study had a rigorous design and randomizing at the nursing-home level then using an administrative database for outcomes was “an efficient use of resources.” The Canadian nursing-home population is likely to be “similar” to the participants in the U.S. study, Dr. Loeb concluded. Complete commentary from Dr. Loeb is presented in the Q&A on page 4.

Professor Stefan Gravenstein, Director of the Division of Geriatrics and Palliative Care at Brown University and last author of the McConeghy study, used the same methodology to focus on high-dose vaccine during the 2013–2014 flu season.8 Published in Lancet Respiratory Medicine in 2017, the high-dose study was funded by Sanofi Pasteur and featured the same number of nursing homes (823), this time with 38,256 participants. The study was powered on respiratory-illness hospitalizations and the primary outcome was “hospital admissions related to pulmonary and influenza-like conditions”. The high-dose vaccine significantly reduced the risk of hospital admissions for pneumonia (RR 0.791; P=0.013; covariate adjusted) and respiratory-related conditions (RR 0.873; P=0.023; covariate adjusted), as well as all-cause hospitalization (RR 0.915; P=0.0028; covariate adjusted).

The two U.S. nursing-home studies are so similar that Canadian physicians may be tempted to use them to compare the effectiveness of high-dose and adjuvanted vaccines; a temptation we must resist, said Dr. Loeb, citing “different seasons, different vaccines.” As noted earlier, the 2016-17 season in the McConeghy study had low vaccine effectiveness, whereas the Gravenstein study took place in 2013-14, which was a well-matched season, with 52 percent effectiveness overall and 54 percent effectiveness against H1N1, the predominant strain.6 Dr. Loeb has advocated for several years for a head-to-head randomized-controlled trial of the two vaccines in Ontario nursing homes. His motivation is to improve patient care and conduct an economic analysis taking into consideration costs of the vaccines (see Q&A, page 4).

In the meantime, retrospective data looking at aTIV versus HD-TIV in older adults became available in August, 2020. A team headed by Dr. Stephen Pelton, a professor of pediatrics at Boston University Schools of Medicine, used linked data from professional fee claims, prescription claims and hospital charges across the continental U.S. to follow the fate of patients after their flu vaccinations in the 2017–2018 season.9 This huge digital fishing net pulled in data from more than 3 million patients and allowed researchers to build a real-world snapshot of outcomes for all the egg-based vaccines used by adults 65+ in the U.S. that season.

The study confirmed that aTIV was significantly more effective than an egg-based, standard-dose vaccine (eTIV) at reducing influenza-related hospital and office visits, pneumonia and other respiratory hospitalizations in U.S. patients aged 65 or more.9 In general, aTIV was more effective than any of the other vaccines, including TIV-HD, at reducing influenza-related office visits and other respiratory-related hospitalizations/ER visits. In this U.S. study, aTIV and TIV-HD were comparable for influenza-related hospitalizations/ER visits and for all-cause and influenza-related costs.9 Study funding was provided by Seqirus.

Real-world Data for Other High-risk Patients

In September, another large retrospective analysis of influenza vaccines provided data on relative effectiveness in high-risk patients, this time for cell-based versus egg-based vaccines.10

For more than 70 years, influenza vaccines have been manufactured in chicken eggs. In response to growing concerns that egg-triggered genetic drift in viral hemagglutinin could be attenuating vaccine effectiveness, cell-based vaccines have started to emerge from the pipeline. One cell-based vaccine is currently available in Canada and the U.S. for the 2020–2021 season (Flucelvax Quadrivalent; QIVc; Seqirus). Other cell-based flu vaccines globally include Celtura (Novartis), Preflucel and Celvapan (Nanotherapeutics) and OptaFlu (Seqirus).

A real-world, retrospective cohort analysis published in Vaccine on September 11, 2020, used administrative claims data from 3,084,062 people in the U.S. to assess the relative effectiveness of egg-based (QIVe-SD) versus cell-based (QIVc) vaccines in the 2017–2018 season.10 Seqirus was the study sponsor. The authors provided a sub-group analysis of high-risk patients aged 4–64, most commonly those with diabetes, chronic heart disease and chronic respiratory disease. QIVc was 10 percent more effective than QIVe-SD against influenza-related hospitalizations/ER visits (n=610,556; P<0.05) and 7 percent superior for all-cause hospitalizations (P<0.0001). Except for hospitalizations for asthma/COPD/bronchial conditions (NS), similar trends were seen for all other respiratory endpoints in these high-risk people. Economic analyses in the paper suggested that annualized all-cause total costs per patient were $471 USD lower for the cell-based vaccine, due to reduced expenditure on medical services.10

Conclusion

The SARS-Cov-2 pandemic shines a spotlight on the vulnerability of high-risk groups to respiratory disease. This has always been the case for influenza. These latest relative effectiveness studies of flu vaccines in these vulnerable patients provide healthcare professionals with timely data on which to base their vaccine decisions as the 2020–2021 flu season starts. Several study authors will be presenting at the upcoming Canadian Immunization Conference (CIC), December 1–3, 2020 (https://cic-cci.ca).

Questions & Answers

Questions and answers on the McConeghy paper5 with Dr. Mark Loeb, FRCPC, MD, MSc, Professor, Pathology and Molecular Medicine, Clinical Epidemiology and Biostatistics, McMaster University.

Q: Which flu vaccine is best for high-risk patients?

Dr. Loeb: It’s an important question. In the elderly, particularly the frail elderly who reside in nursing homes, the optimal vaccine still remains a debate, in that most residents of long-term care facilities [in Canada] will receive inactivated influenza vaccine and often will get standard dose. There are two vaccines that promote more robust immunogenicity and that’s the high-dose and the adjuvanted vaccines.

Q: How would you assess the design of the McConeghy nursing-home study?

Dr. Loeb: The first time they did this [in the 2017 Lancet paper] it was innovative, randomizing at the level of the nursing home and using an administrative database for their outcomes. So it’s an efficient use of resources in my opinion and it’s a rigorous design – it’s a randomized controlled trial. The sample size was adequate to address the questions and the basic designs were fine.

The baseline characteristics were well matched. I think they did a good job on enrollment and randomization. They did specify what their outcomes were clearly, with the limitation that I’m not sure what drove the sample size. Having two primary outcomes was unusual…They do say the study was 90% powered to detect a 25% reduction in respiratory-related

hospitalizations; I generally would take that to be the primary outcome.

Q: How did the poor vaccine match in the season of the study affect the results?

Dr. Loeb: [The study] was launched in 2016–17, and that was a relatively severe influenza season and …it wasn’t a banner year in terms of high efficacy for influenza vaccine, 20 percent or so. And that’s one of the drawbacks of these trials in influenza: you’re really at the mercy of what the event rate is going to be and vaccine effectiveness, depending on what’s in the vaccine and what’s circulating, not to mention the possibility for egg adaptation.

Q: Can we apply these results to Canada?

Dr. Loeb: In terms of the generalizability of the science, I think it’s very similar.

Q: Can physicians use the McConeghy and Gravenstein studies to compare high-dose and adjuvanted vaccines

head-to-head?

Dr. Loeb: One cannot really compare the Gravenstein paper to this one. They’re different seasons, they’re different vaccines. What it says to me is that really what’s required is a head-to-head comparison of high-dose versus adjuvanted vaccine; that would be a really important study. For the last five years I’ve been advocating to do a head-to-head of

high-dose versus adjuvant.

Q: Why is it important to do a trial comparing high-dose with adjuvanted flu vaccine in the elderly?

Dr. Loeb: Because no one’s done that. There is a high-dose randomized controlled trial in the New England Journal [of Medicine], not in nursing homes, but in older people, that had a sizable effect [see Ref. 7]. But there’s never been a study with the adjuvanted vaccine like that…that’s why it’s really important to do a head-to-head comparison.

References:

1. Stall NM, Jones A, Brown K, et al. For-profit long-term care homes and the risk of COVID-19 outbreaks and resident deaths. CMAJ 2020 August 17;192: E946–55; doi: 10.1503/cmaj.201197; early-released July 22, 2020.

2. McGregor MJ, Harrington C. COVID-19 and long-term care facilities: Does ownership matter? CMAJ 2020 August 17;192: E961–2; doi: 10.1503/cmaj.201714; early-released July 22, 2020.

3. Centers for Disease Control. Estimated influenza illness, medical visits, hospitalizations, and deaths in the United States – 2019–2020 influenza season. https://www.cdc.gov/flu/about/burden/2019-2020.html. Accessed October 9, 2020.

4. National Advisory Committee on Immunization (NACI). Canadian Immunization Guide: Influenza and Seasonal Influenza Vaccine for 2020–2021. https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/publications/vaccines-immunization/canadian-immunization-guide-statement-seasonal-influenza-vaccine-2020-2021.html Accessed October 9, 2020.

5. McConeghy KW, Davidson HE, Canaday DH, et al. Cluster-randomized trial of adjuvanted versus nonadjuvanted trivalent influenza vaccine in 823 US nursing homes. Clin Infect Dis 2020 September 3; doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa1233. Published online.

6. Centers for Disease Control. Seasonal flu vaccine effectiveness, 2016–2017. https://www.cdc.gov/flu/vaccines-work/2016-2017.html. Accessed October 9, 2020.

7. DiazGranados CA, Dunning AJ, Kimmel M, et al. Efficacy of high-dose versus standard-dose influenza vaccine in older adults. N Engl

J Med 2014; 371:635–645.

8. Gravenstein S, Davidson HE, Taljaard M, et al. Comparative effectiveness of high-dose versus standard-dose influenza vaccination on numbers of US nursing home residents admitted to hospital: a cluster-randomized trial. Lancet Respir Med 2017;5: 738–46.

9. Pelton SI, Divino V, Shah D, et al. Evaluating the relative vaccine effectiveness of adjuvanted trivalent influenza vaccine compared to high-dose trivalent and other egg-based influenza vaccines among older adults in the US during the 2017–2018 influenza season. Vaccines 2020;8: 446; doi: 10.3390/vaccines8030446.

10. Divino V, Krishnarajah G, Pelton SI, et al. A real-world study evaluating the relative vaccine effectiveness of cell-based quadrivalent luenza vaccine compared to egg-based quadrivalent influenza vaccine in the US during the 2017–2018 influenza season. Vaccine 2020; 38:6334-6343. Epub 2020 July 30.

NEXT REPORT: If you would like to receive an update report on this topic following the upcoming CIC- Canadian Immunization Conference (December 1-3, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada) please e-mail mednet@mednet.ca