Reports

An overview of new guidelines released by the Committee to Advise on Tropical Medicine and Travel (CATMAT) and the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC)

This report is based on medical evidence presented at sanctioned medical congress, from peer reviewed literature or opinion provided by a qualified healthcare practitioner. The consumption of the information contained within this report is intended for qualified Canadian healthcare practitioners only.

MEDI-NEWS Prevention of Japanese Encephalitis in Canadian Travellers

December 2019

In December, 2019, CATMAT released a Statement on the Prevention of Japanese Encephalitis1 for Canadian travellers, following a similar endeavour by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) released in July, 20192. Japanese encephalitis (JE) is a potentially fatal disease transmitted by mosquitoes. Half the world’s population live in JE-endemic regions, mainly Asia and the Western Pacific. Canadian travel-medicine clinicians have access to a JE vaccine, but counselling patients on whether they should vaccinate against this serious but rare disease is challenging. The goal of this newsletter is to summarize the key information in the new CATMAT statement and recent scientific literature on factors to consider when advising Canadian travellers about JE vaccination.

Chief Medical Editor: Dr. Léna Coïc, Montréal, Quebec

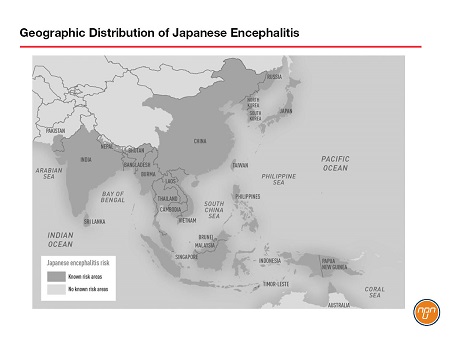

The Japanese encephalitis virus (JEV) is a single-stranded RNA virus of the genus Flavivirus transmitted by Culex mosquitoes. It is the most common cause of vaccine-preventable encephalitis in Asia and much of the Western Pacific. Estimates suggest that there are 70,000 cases each year, 20,000 of which prove fatal. JEV was first described in Japan in the 1870s and today approximately half of the world’s population lives in the 24 countries and island clusters considered endemic for the virus (see Figure 1). There is no specific treatment once JE disease develops, but a prophylactic JE vaccine (IXIARO®) is licensed in Canada.

Figure 1.

Case Study: 21-Year-Old Female with JE

after 4 Weeks in Thailand

(adapted from Turtle et al, 2019)3

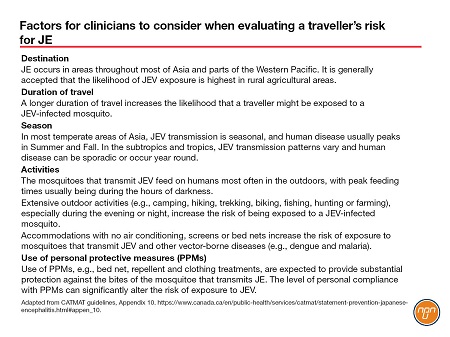

A 21-year-old woman not vaccinated against JE developed a febrile illness after four weeks in Western Thailand in April, 2014. Accommodation was basic and she had many mosquito bites despite using diethyltoluamide (DEET). After being found unconscious in her hotel room she was hospitalized, where she had seizures and a cardiac arrest and was intubated. She remained in hospital for 4 weeks. She underwent neuro-rehabilitation and made a “good recovery” and on day 30 was transferred back to a UK hospital from where she was discharged the following day. JEV serum IgG was positive, with negative IgM/IgG for dengue virus and West Nile virus. Two and a half years later, the patient still had cognitive difficulties, could not remember much of her past and felt exhausted after completing the smallest of tasks. The patient recalled the advice she had received about JE vaccination: “the risk was low and the provider had never heard of anyone affected by JE.” This case study draws attention to the importance of informing travellers about the potential consequences of acquiring JE, in addition to the likelihood, which may vary according to the exact itinerary, duration of travel, the season, the accommodations, and the planned outdoor activities, particularly in the evening and at night (See Table 1. Factors for clinicians to consider when evaluating a travellers’ risk for JE).

Table 1.

Clinical and Epidemiological Features

of Japanese Encephalitis

The probability of developing clinical disease after JEV infection is approximately 1/250, according to the CATMAT guidelines. The incubation period is 5–15 days and once clinical disease develops, prognosis is poor, with a 20–30 percent mortality and long-term neurological/psychological sequelae in 50 percent of survivors. There is no specific antiviral treatment, only supportive care and management of complications. The occurrence of JE is seasonal in temperate climates with the primary period of risk being May through October; however, in tropical regions the risk is year round. The natural enzootic cycle of JEV is between Culex mosquitoes and wading birds. Pigs and, to a lesser extent other domestic animals, act as amplifying hosts, encouraging viral replication and transmission. Humans most commonly get infected by close proximity to such an ‘amplifying circle’. As a result, risk is considered highest in rural areas, and also in rainy/warm seasons when the mosquitoes are most active, and from sunset to sunrise, since Culex is night biting. Humans are considered dead-end hosts since the level of viremia is insufficient for mosquito transmission.

Overall Risk Low, but Sub-Populations

at Greater, Unclear Risk

The risk of contracting JEV for a Canadian travelling to an endemic area is considered to be low, but the exact risk for any particular traveller remains unpredictable. The CATMAT guidelines estimated the overall attack rate of clinical JE in Canadian travellers, based on a single published case between 2006 and 2015, to be 1 in 11.65 million. Estimates for US and European travellers suggest that the overall incidence of JE among persons from non-endemic countries who travel to Asia to be less than one case per 1 million travellers. Higher rates have been estimated for travellers from some countries to particular destinations, with risk estimates for Finnish and Swedish travelers to Thailand of 1 case/257,000 and 1 case/400,000 travellers, respectively.4,5 Persons who stay for prolonged periods in rural areas with active JE virus transmission might have a risk level similar to that of the susceptible resident population.2

The wide variations reported on the risk of exposure to JEV demonstrate some of the limitations in our understanding of the specific risks for any individual traveller.

The Changing Epidemiology of

Japanese Encephalitis

Several review articles published prior to the CATMAT statement have called on guidelines developers to have what one author called “an appreciation of the changing epidemiology of JE infection.”6 The spread of JEV into new environments, changes in agricultural practice and animal vectors, climate change, peri-urban growth, changes in international travel to Asia, personal risk factors, mosquito-vector-free transmission and interactions with other flaviviruses contribute to the evolving and changing epidemiology of JE infections and the risk to travellers.6,7,8

CATMAT was not able to estimate the magnitude of the increased risk of these factors that are likely having a profound – but as yet unknown – impact on the apparent risk of JE for Canadian travellers because relevant data were not available. Thus, the exact level of risk for a specific traveller remains unclear.”

When to Use the JE Vaccine

CATMAT suggests that JE vaccine not be routinely used for travel to endemic areas (Conditional recommendation against; moderate confidence in estimate of effect).

This conditional recommendation reflects, among other things, the poorly defined impact of risk factors such as destination, seasonality, travel itinerary and duration of stay on JE risk, and CATMAT’s belief that travellers could have divergent values and preferences (including willingness to pay) related to use of JE vaccine.

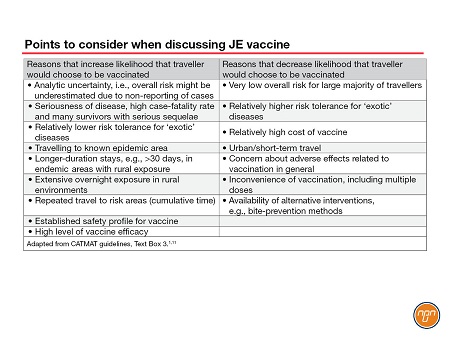

CATMAT recognizes that certain populations, e.g., long-term travellers (e.g., >30 days), travellers who make multiple trips to endemic areas, persons staying for extended periods in rural areas and persons visiting an area suffering a JE outbreak, are likely at relatively higher risk for JE and that more travellers would choose to receive the JE vaccine in these situations. The CATMAT statement provides a list of considerations that may influence decision making related to JE vaccine (See Table 2).

The US Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) also recently released its JE recommendations.2 ACIP recommends the JE vaccine for persons moving to a JE-endemic country to take up residence, longer-term (e.g., ≥1 month) travelers to JE-endemic areas, and frequent travelers to JE-endemic areas. JE vaccine also should be considered for shorter-term (e.g., <1 month) travelers with an increased risk for JE based on planned travel duration, season, location, activities, and accommodations. Vaccination also should be considered for travelers to JE-endemic areas who are uncertain of specific duration of travel, destinations, or activities. ACIP mentions that the JE vaccine is not recommended for travelers with very low-risk itineraries, such as shorter-term travel limited to urban areas or travel that occurs outside of a well-defined JE-virus transmission season.

Counselling Patients on JE

Because CATMAT’s recommendation is conditional, and considering the difficulty for clinicians to determine the exact JE risk for any individual traveller, there is a need for providers to discuss with the traveller the anticipated benefits and harms (including financial costs) associated with JEV to help the traveller reach a decision that is consistent with his or her own values and preferences. The discussion should include potential alternative and/or complementary strategies (e.g., use of personal protective methods against mosquito bites) to vaccination.

Japanese Encephalitis Vaccine

The only JE vaccine available in Canada is IXIARO®, an inactivated Vero-cell-culture-derived vaccine indicated for individuals aged 2 months of age and older. The CATMAT guidelines emphasize the importance of consulting the product monograph9 for IXIARO® and the Canadian Immunization Guide10 before administering the product.

In both adults and children, the primary series of IXIARO® is 2 doses administered at Day 0 and Day 28. In the event the primary series cannot be completed due to time constraints, an accelerated schedule (i.e., first dose at Day 0 and second dose at Day 7) for adults aged 18–65 may be used. CATMAT also suggested a single booster of JE vaccine 12–24 months after the primary series – prior to potential re-exposure to JEV. After receipt of a booster dose, there is evidence that an adequate immune response persists for an extended period among adults. CATMAT therefore suggests that additional booster doses are not necessary for at least 10 years after the initial booster in the situation where protection against JE is desired.

Conclusion

The new CATMAT Statement on the Prevention of Japanese Encephalitis provides guidance for the travel-medicine clinician on this rare, unpredictable, but potentially devastating disease for Canadian travellers. The assessment for JE vaccination presents a challenge for healthcare providers. They must balance the low risk of disease, the uncertainty surrounding the risk factors, the potentially devastating consequences of JE, the possible side effects of the vaccine and the cost of vaccination. The ?nal choice for vaccination rests with travellers, but they should be aware of all the arguments for and against vaccination, including the rare but devastating effects of JE.

Table 2.

Questions and Answers

Questions and answers with Dr. Darin P. Cherniwchan, BSc(Pharm), MD, CM, CCFP, CTH, FCFP, Medical Director of the Fraser Valley Travel Clinic and a member of the Faculty of Medicine, University of British Columbia and the Faculty of Health Studies, University of the Fraser Valley.

Q: When you first mention Japanese encephalitis to a patient heading to an endemic area what do you say?

Dr. Cherniwchan: I first ask, “Are you aware of any insect-borne illnesses (IBIs) that you may be at risk for during this trip?” If the traveller says, “No,” then I explain the main types of viruses/parasites known to exist in the area. I will suggest ways to minimize the risks through vaccinations and personal protective measures (PPMs) such as repellents on skin and permethrin on clothing. If the answer is “Yes,” I will check what he or she knows. Interestingly, in my experience, travellers often overestimate the risk of malaria and underestimate the risk of IBIs such as dengue fever, chikungunya and JE. When the traveller understands the true risks,

I review vaccine options and PPMs. I feel it is my responsibility as a healthcare professional to discuss with each traveller heading to an endemic area the risks, benefits and potential harms (including costs) associated with JE vaccine to help travellers reach an informed decision.

Q: How might you change your approach to JE as a result of the new CATMAT statement?

Dr. Cherniwchan: The current CATMAT statement re-affirms what I have been doing all along when it comes to the prevention of this rare but deadly illness. Survivors are often left with severe, lifelong debilitating neurological sequelae. The vaccine is very safe and I recommend it for those who anticipate travel to JE endemic areas for four weeks or longer (on a single trip or cumulatively). Health economics is a real factor: if a traveller has extended medical coverage for the vaccine, the decision becomes easier. Even if coverage is unavailable, I often see travellers willing to pay out of pocket if cumulative risk exceeds 30 days or if they are planning extensive outdoor activities in rural areas, especially during the evening or night. To improve the cost-benefit ratio of the vaccine, if re-exposure to a JE endemic area is planned or very likely, a third dose of the vaccine can be offered 12–24 months after the initial two doses. This provides an additional 10 years of protection. This ‘sling-shot’ effect is unique to IXIARO® and sharing this information with the traveller often helps with the decision to get the vaccine – particularly if he or she is planning to return to a JE-endemic region.

Q: The guidelines suggest that 'urban' travellers are at less risk. However, three recent review articles6,7,8 highlight the dangers of ‘peri-urban’ business-park encroachment in Asia. How would you advise a business traveller about JE?

Dr. Cherniwchan: JE illness is under-reported and its effects on travellers under-appreciated. Changing agricultural practices and development in peri-urban centres make the epidemiology highly dynamic and the risks unpredictable. Peri-urban business parks are a common destination for the Canadian business traveller. These travellers often lack an awareness of risk, seldom use PPMs and often travel with little or no advance notice. They also tend to travel frequently to the same at-risk destinations, adding to their overall cumulative risk.

Q: In summary, what type of patient would benefit least/most from JE vaccine?

Dr. Cherniwchan: I tend not to recommend the JE vaccine for those who adhere to PPMs and travel strictly to urban areas for short trips of fewer than 30 days (cumulative) and/or those stopping at typical cruise-ship ports of call. Travellers best suited for IXIARO® include:

1. Those with greater than 30 days of cumulative risk to endemic areas or repeated travel to risk areas.

2. People entering regions with known increased activity of transmission.

3. Expats.

4. Travellers planning extensive outdoor activities (e.g., camping, trekking, biking) in rural areas, especially during evening or night.

5. Back-packers, those with uncertain itineraries or those staying in accommodation with no air conditioning, screens or bed nets.

6. Travellers visiting friends and relatives, especially in rural areas. Such travellers tend to significantly underestimate risk and take fewer precautions.

7. Visitors likely to have farm, rural or peri-urban exposures.

References:

1. Statement on Prevention of Japanese Encephalitis. Committee to Advise on Tropical Medicine and Travel (CATMAT) and Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC). Published December, 2019. https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/catmat/statement-prevention-japanese-encephalitis.

2. Hills SL, Walter EB, Atmar RL, Fischer M. Japanese Encephalitis Vaccine: Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. MMWR Recomm Rep 2019; 68(No.2):1–33.

3. Turtle L. et al. ‘More than devastating’ – patient experiences and neurological sequelae of Japanese encephalitis. J Travel Med. 2019; 26:1–7.

4. Lehtinen VA, Huhtamo E, Siikamaki H, Vapalahti O. Japanese encephalitis in a Finnish traveler on a two-week holiday in Thailand. J Clin Virol. 2008; 43:93–95.

5. Buhl MR, Lindquist L. Japanese encephalitis in travelers: review of cases and seasonal risk. J Travel Med. 2009; 16:217–219.

6. Connor BA, et al. Japanese encephalitis vaccine for travelers: risk-benefit reconsidered. J Travel Med. 2019; 26:1–3.

7. Connor B, Bunn WB. The changing epidemiology of Japanese encephalitis and new data: the implications for new recommendations for Japanese encephalitis vaccine. Trop Dis Travel Med Vaccine 2017; 3:14–19.

8. Lindquist L. Recent and historical trends in the epidemiology of Japanese encephalitis and its implication for risk assessment in travellers. J Travel Med. 2018; 25:Suppl.1,S3–S9.

9. Valneva Austria GmbH. IXIARO Product Monograph. 2018

10. Public Health Agency of Canada. Canadian Immunization Guide: Part 4 – Active Vaccines. 2014; Available at: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/publications/healthyliving/canadian-immunization-guidepart-4-active-vaccines/page-11-japanese-encephalitis-vaccine.html.

11. Hatz C, et al. Japanese encephalitis: defining risk incidence for travelers to endemic countries and vaccine prescribing from the UK and Switzerland. J. Travel Med. 2009; 16:200–203.