Reports

Optimizing Immunosuppression Adherence to Improve Long-term Graft Function

This report is based on medical evidence presented at sanctioned medical congress, from peer reviewed literature or opinion provided by a qualified healthcare practitioner. The consumption of the information contained within this report is intended for qualified Canadian healthcare practitioners only.

MEDICAL FRONTIERS - 24th International Congress of the Transplantation Society

Berlin, Germany / July 15-19, 2012

Berlin - Long-term outcomes following transplantation have improved since the early 1980s but challenges remain, including increasing recipient and donor age as well as growing use of expanded criteria donors, all of which impact graft function. Calcineurin inhibitors (CNIs) are the backbone of immunosuppressive therapy. Minimization can cause subclinical inflammation that can lead to development of de novo donor-specific antibodies and potential antibody-mediated rejection, while over-immunosuppression carries a risk of infection, toxicity and malignancy. Optimizing immunosuppression is the most effective strategy to prevent these events. Measures that simplify immunosuppressive regimens and improve adherence, such as once-daily CNI use, may lead to better long-term outcomes.

Current challenges in transplantation medicine include increasingly older donors and recipients as well as growing use of expanded-criteria donor (ECD) organs. Each of these factors is independently associated with poorer outcomes following kidney allograft transplantation. “More and more patients 60 years of age and older are now being transplanted,” confirmed Prof. Gerhard Opelz, Professor and Director, Department of Transplantation and Immunity, University of Heidelberg, Germany, “and older patients clearly do not do as well as younger patients.”

Older patients are also at increased cardiovascular (CV) risk which, at the time of transplantation, is associated with significantly higher risk of CV death. All-cause mortality and major acute coronary events are also significantly more likely to occur in the setting of graft loss than in patients with a functioning graft. More than one-third of all donors in Europe are now classified as ECDs and recipients of these organs have significantly lower graft survival rates than do recipients whose organs do not fall into this category, Prof. Opelz pointed out. Advanced donor age is a very important contributor to graft dysfunction.

The large, randomized OSAKA study is highly representative of patients receiving kidney transplants in Europe today. It showed that donor age was the strongest predictor of whether patients reached the composite efficacy failure end point at week 24, defined as graft loss, biopsy-confirmed acute rejection (BCAR) and graft dysfunction (an estimated glomerular filtration rate [eGFR] of <40 mL/min/1.73 m2). Efficacy failures of <30% were reported for recipients aged <30 years to over 70% when the donor age was >70.

Short- and Long-term Findings

It appears that the impact of acute rejection on long-term graft survival is dependent upon when it occurs. If a rejection episode occurs <90 days post-transplant, studies indicate there is little effect on long-term outcomes. However, even if kidney function normalizes following a rejection episode occurring >90 days post-transplant, “long-term outcome is affected by these rejections,” Prof. Opelz noted.

To attenuate the risk of calcineurin inhibitor (CNI)-induced nephrotoxicity, the use of regimens that do not contain or minimize CNIs is increasing. However, as discussed by Prof. Bengt Fellström, Professor of Nephrology, Uppsala University Hospital, Sweden, physicians must balance the risk of CNI nephrotoxicity against the risk of under-immunosuppression and the subsequent formation of de novo donor-specific antibodies (dnDSAs) and potential antibody-mediated rejection. In his evaluation of trials in which patients were switched largely from a CNI-based to a mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibitor-based regimen, significant improvements in eGFR with mTOR inhibition were typically demonstrated relative to CNI-based therapy. However, with longer-term follow-up, improvements in renal function often disappeared, “suggesting that short-term improvement in eGFR does not necessarily translate into long-term graft survival,” Prof. Fellström told delegates.

Prof. Daniel Serón, Professor of Medicine, Autonomous University of Barcelona, Spain, in turn noted that the prevalence of CNI nephrotoxicity varies substantially from centre to centre, depending on the definition used to characterize CNI nephrotoxicity. In patients receiving organs other than kidneys, glomerulonephritis, diabetic nephropathy and thrombotic microangiopathy are very common.

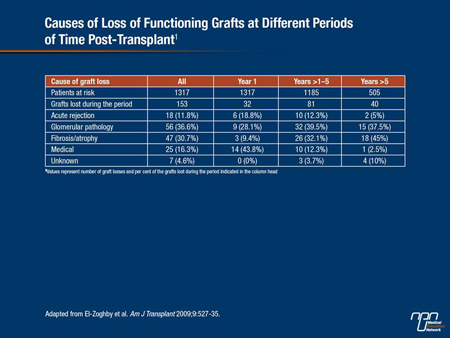

Causes of Kidney Allograft Loss

In one study cited by Prof. Serón (El-Zoghby et al. Am J Transplant 2009;9(3):527-35), investigators looked for specific causes of kidney allograft loss in 1317 kidney recipients. During 50.3 months of follow-up, 330 grafts were lost. Among grafts lost due to graft failure censored by death (n=153), more than two-thirds were due to glomerular diseases and fibrosis/atrophy (Table 1). Only one case of fibrosis/atrophy attributed to CNI toxicity was identified. Prof. Serón also noted that early subclinical inflammation is very common in the transplanted kidney and is a risk factor for progression to chronic lesions and for the development of dnDSAs. “The greater the inflammation in the first biopsy, the higher the risk of progression to interstitial fibrosis and the poorer the outcome,” he told delegates.

Table 1.

“Inflammation is not good news for the kidney. It is associated with progression of fibrosis and a higher probability of antibody-mediated rejection and this is strongly mediated by the type of immunosuppressant a patient receives,” Prof. Serón remarked. Results from Moreso et al. (Transplantation 2004;78:1064-8), for example, showed that the risk of borderline and grades I-II acute rejection were both lower with tacrolimus compared with cyclosporine in patients receiving identical immunosuppression. According to a study cited by Prof. Serón, the probability of developing dnDSAs and antibody-mediated rejection appears to be higher when patients are switched from a CNI-based regimen to one containing an mTOR inhibitor.

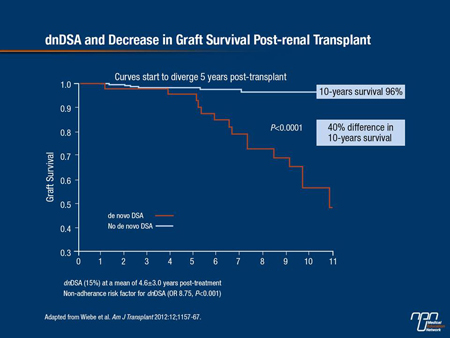

The impact of dnDSA antibodies is not trivial, as reported in a recent Canadian study (Wiebe et al. Am J Transplant 2012;12:1157-67). There was a 40% difference in 10-year renal graft survival rates between patients who developed dnDSAs at a mean of 4.6 years’ post-transplant compared with patients who did not (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

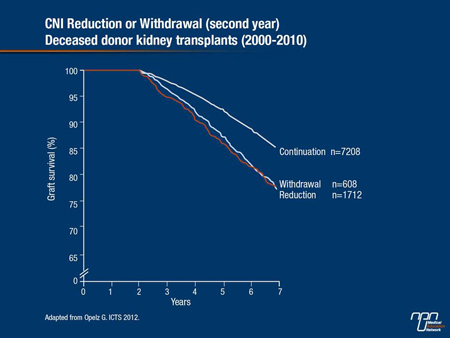

Furthermore, over the past 10 years, European investigators have been collecting registry data on patients in whom CNIs were reduced or withdrawn in the second year following kidney transplantation. Outcomes data clearly indicate graft survival among those who continue on CNI-based immunosuppression is superior relative to those in whom CNIs were either reduced or withdrawn (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

In several hundred patients, European registry data have shown inferior outcomes in patients who have been switched from CNI-based immunosuppression to an mTOR inhibitor (Opelz G, Döhler B. Transplantation 2008;86:371-6). “The switch may be well meant but graft survival after conversion is lower, so you cannot uncritically switch a patient to an mTOR inhibitor because a risk of immune reactivity might occur,” Prof. Opelz remarked.

Prof. Barnhard Banas, Professor of Internal Medicine and Nephrology, University of Regensburg, Germany, agreed with previous speakers, although he stressed that CNI nephrotoxicity should not be trivialized because it does occur in the setting of transplanted organs other than the kidney. “We know that only a small proportion of renal transplant patients really benefit from changing from a CNI to an mTOR inhibitor and this small proportion of patients is not very well defined. You have

to exclude all primary renal disease and all patients with an eGFR <40 mL/min/1.73 m2; this represents the majority of patients we now have in Germany, and if you have a patient with proteinuria, they will probably do worse on an mTOR inhibitor than on a CNI inhibitor. CNIs are not the perfect immunosuppressive drug for transplant recipients but they are still the best drug we have for the majority of patients today.”

Adherence as Primary Factor in the Prevention of dnDSAs

If the development of dnDSAs and potential antibody-mediated rejection is a pivotal event in eventual graft loss over time, then strategies to prevent dnDSAs clearly have the potential to improve long-term graft survival. Adherence is crucial. In Wiebe et al., in which the presence of dnDSAs was associated with a 40% difference in 10-year graft survival, the strongest predictor for the development of dnDSAs was non-adherence, with an adjusted odds ratio (OR) of 8.75 (P<0.001), followed by mismatching of certain class 2 antigens (OR 5.66, P<0.006). Indeed, non-adherence has been identified as the cause of kidney allograft loss in approximately half of all kidney allograft losses (Sellarés et al. Am J Transplant 2012;12(2):388-99).

Study Findings

Given the potential consequences of reduced adherence, compliance is surprisingly poor among many transplant recipients. A study from the psychiatric literature (Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2000;22(6):412-24) found that 20% to 50% of transplant recipients were not fully compliant with their immunosuppressive regimen. Among the factors cited by investigators for non-adherence were the type and number of drugs needed and the number of daily doses required. Single-centre experience indicates that compliance is excellent within the first few months of transplantation and tapers off substantially over time.

In an effort to improve adherence, Dr. Luca Toti, University of Rome-Tor Vergata, Italy, and colleagues (abstract MON.CO11.07) converted 82 liver transplant recipients—none of whom had been treated for a rejection episode prior to conversion and all of whom had stable liver and kidney function—from tacrolimus twice-daily to once-daily, extended-release tacrolimus in a 1:1 fashion. Patients had received their liver transplant at least 6 months prior to conversion and were followed up for at least 24 months.

Mean tacrolimus levels in the majority of patients were significantly lower at 1 and 3 months’ post-conversion (4.4 ng/mL) than baseline (6.65 ng/mL). At 24 months, tacrolimus levels remained lower on the once-daily formulation at 5.1 ng/mL. “Even with these low levels, we had no problems with renal or liver function,” Dr. Toti reported. Glycemic levels were significantly lower at 24 months following conversion.

Perhaps most importantly, more patients consistently took their medication as prescribed following conversion. Prior to conversion, 78% of patients indicated that they had forgotten to take their medication at least once during the previous 4 weeks and over two-thirds indicated that the evening dose was the more problematic to remember. Following conversion, only 23% of patients indicated they had forgotten to take a dose during this same 4-week interval. Patient satisfaction was also high, with only 5 patients indicating there was no advantage to being converted to a once-daily vs. a twice-daily regimen. “This study suggests conversion is good for patients and with lower tacrolimus levels following conversion, maybe we will have a better side-effect profile as well,” Dr. Toti concluded.

Two single-centre reports support the benefits of converting liver transplant patients from twice-daily to once-daily tacrolimus. Volpes et al. (abstract MON.CO11.06) converted 186 stable transplant patients from twice-daily immediate-release tacrolimus to the once-daily extended-release formulation at a median time of 3 years post-transplantation. Median trough blood levels in 166 out of 186 patients sampled were higher prior to conversion (6.3 ng/mL compared to 4.5 ng/mL after conversion); in addition, the mean total daily doses of the once-daily formulation decreased throughout the study period.

A separate group of investigators (Giannelli et al., abstract TUE.MO15.02) evaluated tacrolimus trough levels (among other parameters) at 1, 3, 6, 12 and 24 months after 65 patients were converted from twice-daily to once-daily tacrolimus at a median of 39 months following transplantation. Blood trough levels stabilized in 90% of patients within 45 days following conversion and liver function, blood glucose, lipids and blood pressure remained stable during the 24-month follow-up. Blood trough levels following conversion were again lower than baseline although they remained adequately immunosuppressive for stable liver transplant recipients, observed Prof. Valero Giannelli, Sapienza University of Rome. “We also saw an amelioration in renal function,” he added, from an eGFR of 71 mL/min/1.73 m2 at baseline to an eGFR of 82 mL/min/1.73 m2 at month 24. “If we can ameliorate or stabilize kidney injury in our transplant patients, that’s a bonus.”

Similar results were reported by Kramer et al. (abstract WED.CO41.09) who analyzed findings from a combined database involving close to 1300 renal transplant recipients. Participants were treated with similar immunosuppressive regimens (with the exception of the CNI component) in which twice-daily immediate-release tacrolimus was compared with the once-daily extended-release formulation. At 24 weeks, the incidence of BCAR at 13.9% in the once-daily group was virtually identical to the BCAR rate of 14.1% when patients were taking the drug twice a day, as was the per cent of patients who reached the composite end point (graft loss, BCAR, loss to follow-up) at 21.5% vs. 19.8% for the once-daily vs. twice-daily group, respectively. The percentage of patients reaching the European Medicines Agency composite end point (graft loss, BCAR, renal dysfunction) at 40.3% and 38.3% for the once-daily vs. twice-daily groups was also similar.

Investigators concluded that findings from this large database of kidney transplant recipients demonstrated non-inferiority of extended-release tacrolimus compared to the immediate-release formulation.

Summary

The greatest challenge in transplantation today is a shortage of donor organs. In the meantime, physicians need to maximize the use of organs they do acquire and provide the most effective immunosuppression possible to preserve long-term graft function. It now appears that the most effective regimen is one a patient can adhere to consistently and strategies to improve adherence should become a priority.