Reports

Pediatric Nutrition

This report is based on medical evidence presented at sanctioned medical congress, from peer reviewed literature or opinion provided by a qualified healthcare practitioner. The consumption of the information contained within this report is intended for qualified Canadian healthcare practitioners only.

RESOURCE LINE

December 2011

Prebiotic-supplemented formula to promote beneficial gut flora in nonbreast-fed infants

Supplementing full-term infant formula with a prebiotic increases beneficial bacteria in the gut and results in stools similar to those of breast-fed neonates without affecting weight gain, according to a systematic review of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) comparing formula milk with and without supplemental prebiotics.

Dr. Shirpada Rao, King Edward Memorial Hospital for Women, Perth, Australia, and multicentre colleagues identified 11 RCTs, 9 of which evaluated the effect of prebiotic supplementation on colony counts of bifidobacteria in the stools.1 As the authors explained, bifidobacteria and lactobacilli prevent growth of harmful bacteria in the gut and early colonization is thus a critical determinant of the permanent gut flora that may affect the infant’s health throughout life.

“Six trials demonstrated significantly higher levels of bifidobacteria after supplementation with prebiotics,” they reported. Two others reported that the prebiotic-supplemented group had a higher percentage of bifidobacteria in the total bacterial count, though not significantly so; 1 trial did not find any significant differences between the 2 groups. There was also a trend in a reduction of pathogenic bacteria in the prebioticsupplemented group, they added.

Eight trials evaluated the effect of prebiotic supplementation on stool pH and all except 1 found prebiotic supplementation resulted in a significant reduction in stool pH compared with controls.

Several of the trials also assessed stool consistency. Of those studies which did, all reported softer stools in the prebioticsupplemented

group vs. controls. Stool frequency was also higher and similar to the frequency in breast-fed infants, they added. All but 1 trial also found that the prebioticsupplemented formula was as well tolerated as control formula. In that trial,2 group 1 received polydextrose (PDX), GOS (galactose oligosaccharide) and LOS (lactulose) while a second group received double the dose of the same 3 supplements. A third group received standard formula. There was a higher risk of diarrhea and eczema in the prebiotic group 1 and a higher risk of excessive irritability in prebiotic group 2 compared to the standard formula group.

Human milk contains at least 100 different oligosaccharides that promote beneficial gut flora, making breast-feeding very important, especially in the first month of life. If breast-feeding is not possible, a formula with prebiotics may be beneficial in helping the infant gut colonize with bifidobacteria and lactobacilli, beneficial bacteria that tend to be more abundant in the gut of the breast-fed infant.

Lutein-supplemented formula and retinal health

Mothers who are already formula-feeding may wish to consider the benefits of a lutein-supplemented formula in order to help their infant achieve optimal retinal health.

In a recent Webinar sponsored by Abbott Nutrition, Dr. Billy R. Hammond, PhD, Vision Sciences Laboratory, University of Georgia, Athens, explained that humans cannot synthesize lutein, a carotenoid that is important for eye health. “This means that the only sources of lutein (for infants) are breast milk and luteinsupplemented formula before solid foods are introduced,” he said.

Most carotenoids are obtained from leafy green vegetables. “This is again important,” Dr. Hammond added, “as the typical North American diet is low in leafy green vegetables.”

For example, when investigators measured levels of lutein and zeaxanthin, the only other carotenoid that accumulates in eye tissue, in college students, they found average levels of both carotenoids were very low.3 When the same investigators supplemented the students with 12 mg/day of lutein and zeaxanthin, a steady increase in eye levels of these carotenoids was noted.4

Dr. Hammond also noted that one of the prominent omega-3 fatty acids in the brain and eye is docosahexaenoic acid (DHA). “DHA is a highly oxidizable lipid so it has to be protected by antioxidants,” he explained. Lutein and zeaxanthin are potent antioxidants and are thought to protect DHA from peroxidation. Protection against peroxidation is especially critical in infancy as the retina is highly metabolically active and subject to significant amounts of oxidative stress during this period. Furthermore, infants have extremely clear lenses, permitting large amounts of damaging sunlight to reach the retina.

Pigments in the eye are also exactly where they need to be to have an effect on visual processing, as Dr. Hammond noted. Lutein and zeaxanthin, yellow pigments, absorb intraocular scattered light, an important filtering function as scattered light is one of the major factors that limits visual performance. In a study carried out by Hammond and colleagues, researchers found a “very significant correlation” between levels of lutein and zeaxanthin and glare disability.4,5 Again, when the same subjects were supplemented with lutein,the degree of glare disability appreciably decreased—“suggesting a causal link between the filtering action of lutein and zeaxanthin and glare problems,” Dr. Hammond reported.

Another visual processing function over which both carotenoids have considerable influence is photo stress recovery, a measure of how quickly subjects recover from exposure to blinding light. Following lutein supplementation, investigators found that photo stress recovery times proportionately decreased as the amount of pigment in the retina increased.4

Lutein and zeaxanthin also affect chromatic performance. As Dr. Hammond explained, edges are critical in vision. Indeed, the visual system is designed to enhance the appearance of edges so that people can define objects; when edges become indistinct, “you lose your ability to see.” Pigments enhance chromatic borders, allowing people to distinguish between edges, he added.

Other research conducted by Dr. Hammond6 has shown that the presence of the same 2 carotenoids in the brain, where they also

accumulate, could influence neural efficiency and the processing of information.

Hydrolyzed infant formula decreases diabetes-associated autoantibodies in genetically primed infants

Weaning newborn infants who are genetically predisposed to develop type 1 diabetes to a highly hydrolyzed formula decreases their likelihood of developing diabetes-associated autoantibodies compared with weaning them to a cow’s milk-based formula, according to a

randomized double-blind trial.7

Dr. Mikael Knip, Hospital for Children and Adolescents, Helsinki, Finland, and multicentre colleagues assigned 230 infants with a first-degree relative who had type 1 diabetes to receive the intervention formula or a control formula whenever breast milk was not available. The intervention formula was an extensively hydrolyzed casein-based formula while the control formula consisted of 80% intact milk protein and 20% hydrolyzed milk protein. “Breast-feeding was encouraged and exceeded the national average in both study groups,” the authors noted.

The median age of infants on introduction of formula was 2.6 months in the casein hydrolysate group and 1.1 months in the control group while the median age when the intervention was completed was 7.4 months and 6.4 months, respectively. Blood samples were obtained at multiple follow-up visits and children were observed up to 10 years of age. Along the way, blood samples were assessed for the presence of autoantibodies to insulin plus a number of other diabetes-related autoantibodies.

“At least 1 autoantibody developed in 17 of the children in the casein hydrolysate group and 33 in the control group,” investigators reported. In addition, 8 children in the intervention formula group tested positive for 2 or more autoantibodies vs. 17 for those in the

control group. Thus, the unadjusted hazard ratio (HR) for positivity for 1 or more autoantibodies in the intervention group was 0.54 vs. controls while the HR adjusted for the difference in duration of exposure to the study formula was 0.51, as the authors pointed out. For positivity for 1 or more autoantibodies, the unadjusted and adjusted HR in favour of the intervention formula was 0.52 and 0.47, respectively.

By the time children were 10 years of age, 6% of those in the casein hydrolysate group vs. 8% in the control group had developed type 1 diabetes, so the risk for type 1 diabetes was not significantly associated with the feeding intervention. The number of children in the per-protocol cohort—i.e. the cohort defined as the subjects who completed the study and progressed to type 1 diabetes—was 4% in the casein hydrolysate group vs. 8% in the control group. Of the 13 children in the per-protocol cohort in whom diabetes developed, all but 1 had samples that tested positive for multiple autoantibodies in the preclinical period, as investigators also indicated. Positivity for 2 or more antibodies signals a risk of 50 to 100% for the development of type 1 diabetes over the course of 5 to 10 years. A short duration of breast-feeding and early exposure to complex dietary proteins have both been implicated as risk factors for advanced beta-cell autoimmunity or clinical type 1 diabetes.

“Our results indicate that a preventive dietary intervention aimed at decreasing the risk of type 1 diabetes may be feasible,” the authors stated. Such an intervention would need to be initiated early in life, they added, since the first signs of beta-cell autoimmunity may appear before a child reaches the age of 3 months.

Nevertheless, if an intervention such as that one used in this study could be proven safe and effective in high-risk children, “the next step might be to expand the intervention to a wider infant population, since 83 to 98% of children with newly diagnosed type 1 diabetes are from the general population.”

Pregnancy and weight gain

Health care professionals need to counsel women that pregnancy is not a license to “eat for 2” and that how much weight they should gain during pregnancy is based on their body mass index (BMI) prior to pregnancy and not blanket rules.

As noted by Health Canada, a healthy weight gain during pregnancy not only optimizes initial health for the infant but also reduces the risk of complications both in pregnancy and at delivery, and improves the mother’s long-term health. Excess gestational weight gain is associated with higher rates of caesarean section, preterm delivery and large-for-gestational-age infants.

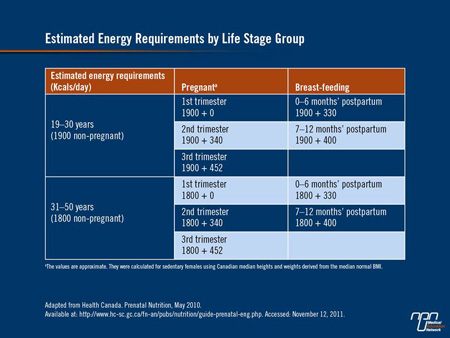

Excess gestational weight gain is also associated with postpartum weight retention, which in turn increases the likelihood of entering a future pregnancy overweight or obese, with their associated morbidities. The amount of weight a woman should gain during pregnancy can be calculated using the Pregnancy Weight Gain Calculator which can be summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

The Canadian Maternity Experiences Survey carried out in 2006 showed that women who gain less-than-recommended amounts of weight during pregnancy are approximately twice as likely to give birth to infants weighing less than 2500 g than they are to give birth to normal-weight infants. On the other hand, many Canadian women gain more weight than is recommended: in the same survey, over half of women who were overweight prior to pregnancy gained more weight than is recommended. Some 40% of women who were normal weight at baseline also gained more than recommended amounts of weight as did about 25% of women who were underweight prior to pregnancy.

This is perhaps understandable as during pregnancy, energy requirements do not increase until the second trimester; at that point, women who are at a normal body weight prior to pregnancy need only an additional 350 calories/day during the second trimester and an additional 450 calories/day during the third trimester to support fetal growth and development. Women who breast-feed also need an additional 450 calories/day to support optimal infant growth.

Nutritional supplementation with essential micronutrients during pregnancy, lactation

Recommendations to use a nutritional supplement containing a good source of protein and essential micronutrients may help ensure maternal nutrient needs are met during pregnancy and lactation and consequently the infant’s as well.

As noted by Neggers and Goldenberg,8 considerable evidence suggests micronutrients play an important role in pregnancy outcomes. “Even in a developed country like the US, a substantial proportion of women of childbearing age consume diets that provide less than the recommended amounts of micronutrients, particularly zinc, folate, calcium and iron,” the authors noted. Nutrient requirements also increase during pregnancy in order to support fetal growth and maternal health, as noted by the National Institutes of Health in their Dietary Supplement Web site.

It is well established that folic acid (or folate as it naturally occurs in the body) is vital for the prevention of neural tube defects. Taken prior to and shortly after conception, folic acid has also been shown to reduce congenital heart defects, cleft lip and urinary tract anomalies and may also improve cognitive function. Folate deficiency during pregnancy in turn may increase the risk of preterm delivery, fetal growth retardation and low infant birth weight.

Iodine is probably the most critical nutrient for normal mental development as iodine deficiencies in pregnancy can lead to cretinism and neuromotor delays in infants. Iron requirements also approximately double during pregnancy because of increased blood volume and greater needs of the fetus. Blood loss during delivery also increases the need for iron. If iron intake does not meet increased requirements, iron-deficiency anemia can occur, a disorder associated with significant morbidity including preterm delivery and low birth weight infants. Iron supplementation can, however, reverse iron-deficiency anemia in pregnancy.

Zinc helps the body repair itself and overcome infection, a bonus in young infants whose immature immune system places them at greater risk for infection, including some of the most serious of childhood infections such as meningitis. Choline, another micronutrient in food, serves as the starting material for several metabolites that play key roles in fetal development, particularly the brain. Existing data show that the majority of pregnant and lactating women are not achieving choline target intake levels of between 450 and 550 mg/day during pregnancy and lactation, respectively.9 As choline is not found in most varieties of prenatal or regular multivitamins, increased

consumption of choline-rich foods or a balanced nutritional supplement containing choline may be required to meet high preand postnatal demands.

Calcium and vitamin D support the development of strong bones and teeth. New recommendations by Health Canada indicate that pregnant and lactating women should consume 1300 mg of calcium to an upper limit of 3000 mg if they are between 14 and 18 years of age; between 1000 and an upper limit of 2500 mg if they are between 19 and 50 years of age; and between 600 IU and an upper limit of 4000 IU of vitamin D.

References

1. Rao S, Srinivasjois R, Patole S. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2009; 163:755-64.

2. Ziegler et al. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2007;44(3):359-64.

3. Hammond BR, Caruso-Avery M. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2000; 41:1492-7.

4. Stringham JM, Hammond BR. Optom Vis Sci 2008;85:82-8.

5. Stringham JM, Hammond BR. Optom Vis Sci 2007;84:859-64.

6. Renzi LM, Hammond BR. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt 2010;30:351-7.

7. Knip et al. N Engl J Med 2010;363:1900-8.

8. Neggers Y, Goldenberg RL. J Nutr 2003;133:S1737-S1740.

9. Caudill MA. J Am Diet Assoc 2010;110:1198-206.

Questions and Answers

With Sonja Wicklum, MD, CCFP, FCFP

Assistant Professor of Family Medicine, University of Ottawa

Weight Management Clinic, Bariatric Centre of Excellence,

Ottawa Civic Hospital, Ontario

Q: Many women do not eat well during pregnancy. Would they be at risk for micronutrient deficiencies?

A: It depends on whether or not they are taking a prenatal vitamin, the key nutrient being folate. Women should take it prior to conception because the development of the nervous system begins very early on after conception, so women want their folate levels to be high prior to conception and then take it throughout pregnancy. The recommended dose is 400 mcg because women get folate from a lot of foods, especially leafy green vegetables. We are also now talking about omega-3 fatty acids such as DHA, and women should be getting about 200 mg of DHA per day, which works out to 1 or 2 servings of fish a week. However, most of our ocean and inland fish have an element of mercury in them, and mercury is toxic, so if women aren’t eating fish, they need to consider a supplement. Iron needs basically double during pregnancy so we want women to get about 30 mg a day of iron, especially if they are anemic during pregnancy, which is fairly common. Calcium and vitamin D are both important and there are recommendations for zinc and copper as well, but we don’t see deficiencies in copper or zinc in this country, nor are there iodine deficiencies here.

Q: How do you get your patients to stay within the healthy weight gain range during pregnancy?

A: Women need to understand that during the first trimester, they only need an additional 100 calories and during the second and third trimester, they need an additional 350 to 450 so it’s not that much; women simply can’t fall back on thinking they are eating for 2. There has been an effort to educate health care professionals to spend more time with pregnant women and if they are heading off the weight charts, to look at their nutrition and stop the weight gain. We tell our women that pregnancy is a great time to improve their nutrition, not increase it. Women also need to ensure that each meal is well balanced: they need fruit, vegetables, protein and good source of carbohydrates and to avoid sweets taken on a regular basis. In our bariatric centre, we see many women who gained a lot of weight during pregnancy and they just never took it off, so gaining too much weight in pregnancy can be a lifechanging event. Women have to stop thinking, “I can do whatever I want because I’m pregnant.” Women can also have a lot of reflux during pregnancy and they graze all day long because it makes them feel better. They need to talk to their doctor and have that reflux treated because if they continue to graze, their calorie intake will be too high.

Q: Is there a role for nutritional supplement for women during pregnancy and if so, which women do you feel

should consider using the supplement?

A: People often don’t have breakfast so if women are skipping breakfast, Similac Mom is better than not having breakfast or popping in somewhere for a coffee and muffin. Similac Mom is also a good source of protein at 12 g per bottle and it is not high in calories, so if they need a snack, it’s better to grab a bottle of Similac Mom than to reach for a snack that is likely to be much higher in fat and calories. Women often don’t get enough protein in their diet overall and they still don’t eat enough protein when they get pregnant. [However,] people need to understand that protein is much more filling than carbohydrates, it lasts longer and will keep energy going for much longer so it’s a good choice, especially if women get hypoglycemic during pregnancy which protein-rich foods can help offset.