Reports

Asthma Control: Taking the Long-term View

This report is based on medical evidence presented at sanctioned medical congress, from peer reviewed literature or opinion provided by a qualified healthcare practitioner. The consumption of the information contained within this report is intended for qualified Canadian healthcare practitioners only.

PHYSICIAN PERSPECTIVE - Viewpoint based on presentations from the Family Medicine Forum 2011 (College of Family Physicians of Canada)

Montréal, Quebec / November 3-5, 2011

Guest Editor:

Charles K.N. Chan, MD, FRCPC, FCCP, FACP

Vice-President, Medical Affairs & Quality

University Health Network

Professor and Vice-Chair of Medicine

University of Toronto

Toronto, Ontario

Introduction

The concept that asthma is a chronic disease is often inadequately expressed to and poorly understood by patients. Focusing solely on symptom avoidance may lead patients and their physicians to a false sense of security about the level of control achieved. Health care practitioners should communicate the importance of day-to-day asthma control and avoidance of asthma exacerbations as ways to limit future risk, in the same way they convey the need for long-term treatment of other chronic diseases or of cardiovascular risk factors. It is possible to select a regimen that meets the patient’s medical and lifestyle needs. Strategies for maintenance therapy that combine an inhaled corticosteroid (ICS) and a long-acting beta agonist are an effective option for patients whose asthma is poorly controlled on ICS alone.

Asthma is a chronic disease characterized by airway hyperresponsiveness and symptomatic episodes of varying severity that may include wheezing, coughing, chest tightness and breathlessness. Inflammation is present in the airways even in the absence of symptoms. Persistent inflammation may lead to remodelling which, over the long term, may have a deleterious effect on lung structures and patient outcomes.

Chronic Inflammation

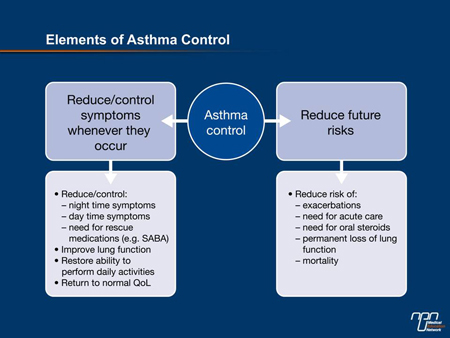

As was mentioned by several speakers at the 2011 Family Medicine Forum held in November in Montréal, the concept that asthma is a chronic disease is often poorly understood by patients. People with asthma often believe that in the absence of symptoms, they do not have the disease; or that if they have only minimal symptoms (or avoid activities that may lead to symptoms), medication is optional. Considering only day-to-day comfort, defined by the presence or absence of symptoms and exacerbations, leads patients (and sometimes their physicians) to a false sense of security about the level of control achieved. This narrow focus also neglects the notion that future risk related to asthma can and should be prevented (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Lack of awareness of asthma pathology and the need for ongoing suppression of inflammation may lead patients to avoid, reduce or stop taking crucial maintenance therapies, thereby increasing the risk of symptoms, exacerbations and complications, including death. According to a 2006 survey by the Asthma Society of Canada, about 1 in 3 patients with asthma did not plan to fill their prescription for an inhaled corticosteroid (ICS) for maintenance therapy, and about 20% of patients who do have the medication on hand do not take it.

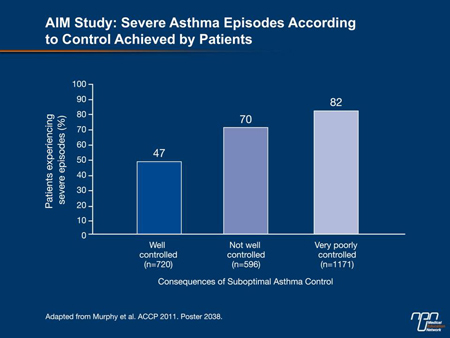

A report presented at the 2011 American College of Chest Physicians meeting (Murphy et al., Poster 2038) demonstrated how such behaviour can promote future risk. US investigators determined that 69% of 2500 patients in the Asthma Insight and Management (AIM) survey had experienced a severe asthma attack in the 12 preceding months. Among patients with “very poorly controlled” or “not well controlled” asthma, the incidence of severe episodes was 82% and 70%, respectively, compared with 47% for patients with good control (Figure 2). More than one-third of patients had felt their life was in danger during the severe episode. This study supports previous findings that poor control of asthma symptoms increases inflammation and therefore patients’ risk for future exacerbations and associated medical needs such as acute care and oral steroids, as well as permanent loss of lung function and mortality.

Figure 2.

Control: Perception vs. Reality

Several recent studies have also confirmed that although great strides have been made in the understanding and treatment of asthma, relatively few patients do have well-controlled disease. Many tolerate a disturbing level of symptoms while still describing their condition as “under control.” Of the 2400 patients (or their parents) responding to the EUCAN-AIM survey (www.takingaimatasthma.com), for example, 93% reported that their asthma was controlled, while 7% said it was poorly or not controlled. However, the data collected tell a different story. At least half the patients had experienced an event in the previous months that suggested poor asthma management; 45% had seen a physician due to worsening symptoms; 39% had experienced a severe asthma episode; 28% had sought emergency care for asthma symptoms; and 5% had been hospitalized for at least 1 night.

As further evidence of poor control in this population, a substantial percentage of respondents reported that their asthma continued to have a negative impact on sleep (42%) or their ability to exert themselves (60%), take part in social activities (37%) or perform daily tasks such as shopping (42%). That only about 55% of patients responded to a question about the effect of their asthma on their involvement in sports and recreation suggests that many simply do not take part in these potentially beneficial activities in an attempt to avoid symptoms.

Overuse of rescue medication for asthma was also evident among Canadian EUCAN-AIM respondents. The mean number of quick-relief inhalers used per year was 6 (median, 3). This finding can be linked to the misguided but widespread penchant among patients to take medication only on an as-needed basis.

The EUCAN-AIM data support earlier findings in the TRAC study (Fitzgerald et al. Can Respir J 2006;13:253-9) that while 97% of patients believe their asthma is controlled, on careful assessment only about 53% of cases can be so described. Interestingly, the TRAC study also found that physicians overestimated the level of control achieved in their asthma patients, perhaps indicating an overreliance on self-reporting by patients as compared with objective investigations or detailed queries recommended by Canadian asthma guidelines.

Minimizing Symptoms and Future Risk

Guidelines for the management of asthma call for all patients to be prescribed a fast-acting bronchodilator for use on demand as well as anti-inflammatory daily maintenance therapy. The dosing of ICS, long-acting bronchodilator or leukotriene receptor antagonist (or appropriate combinations of these) is determined first by patient age and then ongoing assessment of control as determined by daytime and nighttime symptoms and the need for rescue inhalations, occurrence of exacerbations, ability to perform physical activity and attend work or school, and measures of lung function. The aim is for most patients to live a normal life, with minimal asthma symptoms on most days. With correct therapy and good adherence, most patients should be able to achieve this goal and prevent the future risks associated with poorly controlled asthma.

Combination Therapies

For adults and children over age 12 whose symptoms are not controlled on current therapy, combination inhalers that contain both an ICS and a long-acting beta agonist (LABA) are a convenient option that may be more effective than the use of separate devices and better tolerated than simply increasing the dose of ICS. Inhalers containing fluticasone/salmeterol, budesonide/formoterol and mometasone/formoterol have all been shown to have better effects on 1-second forced expiratory volume (FEV1) than the component agents used individually. Fluticasone/salmeterol (dry powder or inhaled aerosol formulation) and budesonide/formoterol (dry powder)

significantly increased the number of days and nights without asthma symptoms (Kavuru et al. J All Clin Immunol 2000;105:1108-16, Noonan et al. Drugs 2006;66:2235-54). They have been available in Canada for several years.

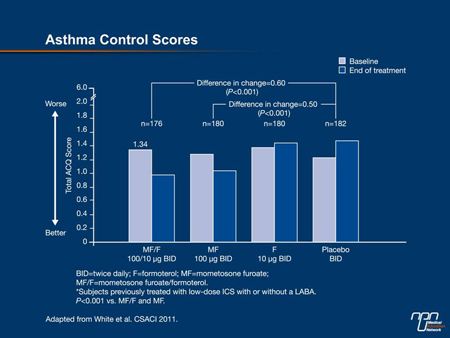

Figure 3.

Mometasone is a potent inhaled steroid, with a high affinity for glucocorticoid receptors and a long duration of action. As formoterol has the most rapid onset of the LABAs, patients tend to appreciate the sensation that the medication is working immediately upon administration.

Several studies presented at the 2011 Canadian Society of Clinical Allergy and Immunology meeting evaluated this combination, an inhaled-aerosol formulation of which was introduced recently in Canada. At all doses (100/10 μg b.i.d., 200/10 μg b.i.d., 400/10 μg b.i.d.), the combination led to clinically meaningful improvements in control, as defined by Asthma Control Questionnaire (ACQ) scores, in patients previously taking low, medium or high doses of ICS (White et al., Poster 16) (Figure 3). In patients whose asthma was not controlled on a previous ICS regimen, the combination was associated with less asthma deterioration than placebo or either component used as monotherapy (Weinstein et al., Poster 13). It was also shown to reduce the need for short-acting beta agonist administration during the day and at night, as well as nighttime awakenings that can lead to impaired daytime performance (Nayak et al., Poster 15, Pearlman et al., Poster 14).

Engage the Patient

Over the past decade or so, the range of effective treatment options for asthma has expanded greatly and it is possible to tailor the regimen to meet the patient’s medical needs and lifestyle. Selection of therapy must take into account factors related to patient preference, such as convenience and simplicity, e.g. no more than twice-daily dosing or metered-dose vs. dry-powder inhaler. A factor that is important to many individuals—partly explaining the widespread overuse of rescue inhalers—is a sensation that the medication is working immediately upon administration. While many patients may express anxiety about using corticosteroids, the doses involved in daily asthma therapy are so low they may be described as homeopathic; and steroid-sparing strategies are available.

Still, any medication must be taken as prescribed to produce the desired results. Good inhaler technique must also be reviewed and reinforced frequently, as errors are very common.

In asthma, as is the case in other chronic diseases, the patient’s engagement in his or her own management is of utmost importance. Our dialogue with patients should be framed in a way that makes the crucial point that asthma, like other chronic conditions such as hypertension and hyperlipidemia, can threaten life and reduce quality of life in the long term; and that treatment must be consistent and lifelong. I hesitate to exhort my colleagues to “scare” their patients, but it is appropriate to discuss the reality of future risks; and explain that asthma deaths, while fortunately rare, may be more likely in patients with poorly controlled mild to moderate asthma than in those with severe disease (Robertson et al. Pediatr Pulmonol 1992;13:95-100, Jorgensen et al. Pediatr Pulmonol 2003;36:142-7). Physicians and asthma educators must endeavour to ensure patients fully understand the meaning of asthma control, the short- and long-term risks associated with a lack of control and especially that good control is achievable.

Questions & Answers

The following questions-and-answer session was conducted with family physicians Dr. Jacques Bouchard, Clinique médicale familiale de La Malbaie, Quebec, and with Dr. Anthony Ciavarella, private practice, Aldergrove, British Columbia.

Q: How do you suggest primary care physicians can best assess their patients’ asthma control in the busy office setting?

Dr. Bouchard: Primary care physicians should definitely use supporting tools in order to systematically check whether the criteria for asthma control are met. Such tools are quite easy to use.

Dr. Ciavarella: Use the mnemonic DNA FREE. First ask about the typical daytime asthma symptoms: wheeze, breathlessness, chest tightness and cough. Next, ask about nocturnal symptoms and especially their effect on sleep quality and daytime fatigue (as well as mood and irritability if sleep is poor). The next question relates to activity intolerance, especially any limitation on usual daytime exercise and social activities. The fourth parameter for assessing control is respiratory air flow. Although the gold standard includes FEV1 and spirometry, peak expiratory flow is simple and acceptable for both diagnosis and office follow-up. The fifth parameter is the need for fast-acting bronchodilator for rescue. The final factors include recent exacerbation or loss of time that would normally be devoted to employment or education. The first five parameters (DNAFR) are elements of the asthma control score.

Q: Why and how do you personalize asthma therapy for your patients?

Dr. Bouchard: It is important for physicians to know their patients well, i.e. their personality, the type of work they do, their treatment preferences, their lifestyle, their socio-economic status, etc. Young and active patients like fast-acting treatments that give them persistent relief. Patients who love sports should be cautioned that humidity may create problems with some dry powder devices. Some patients are also concerned with their image [and this can influence treatment selection].

Dr. Ciavarella: A successful action plan will teach the patient to measure their own asthma control and adjust therapy, avoid triggers where possible, as well as establish for the patient a cause and effect pattern for symptom relief for daytime, nighttime and activity parameters. All patients need treatment for asthma control, usually a corticosteroid or an LTRA or both. The proper dose of a corticosteroid is the safe dose needed to get the job done.

Q: Are there particular situations or unmet needs in your patients for which the new combination of mometasone/formoterol would be especially suitable?

Dr. Bouchard: This combination therapy would certainly suit patients who are looking for fast symptom relief and whose sole reason for adhering to therapy is that their symptoms are relieved immediately. In addition, patients who already use a metered-dose inhaler for rescue therapy prefer to have the same kind of device for maintenance therapy.

Dr. Ciavarella: If the patient and physician believe quick medication action is appropriate, the treatment plan should include combination therapy (both ICS and LABA). If the latter agent also has fast-acting β2 agonist properties (as is the case with formoterol in the new mometasone/formoterol combination), this simplifies the plan.

Q: What is the best way to explain the “future risk” concept to patients?

Dr. Bouchard: We have to explain to patients that they could eventually feel as if they were having a permanent asthma exacerbation because their airways have “hardened” and have stopped responding to treatment. Patients would then have to limit their activities for life.

Dr. Ciavarella: The principal reason that patients seek medical advice is that they are seeking daytime symptom relief. Surprisingly, they do not always equate poor sleep or inability to tolerate activities with asthma. Therefore, there is an opportunity to increase their expectations from asthma control. Patients must understand that asthma is a chronic disease and episodes of worsening will continue to occur. Addressing the future risk begins with long-term daily ICS. Patients should learn that the most critical and beneficial facets of good control are getting the lungs to grow to their best capacity and keeping that lung capacity for life. We buy life insurance to cover the loss of wealth with death; can we not buy into lung insurance to cover the gain of health in living?