Reports

Influenza in the Elderly: Seeking More Effective Vaccine Strategies

This report is based on medical evidence presented at sanctioned medical congress, from peer reviewed literature or opinion provided by a qualified healthcare practitioner. The consumption of the information contained within this report is intended for qualified Canadian healthcare practitioners only.

PRIORITY PRESS - 11th Canadian Immunization Conference

Ottawa, Ontario / December 2-4, 2014

Ottawa - Elderly patients are at high risk for developing influenza and its complications, which can include increased frailty after hospitalization. Immunization in this population is vital, despite the fact that immune senescence lowers the effectiveness of vaccines. As increasing numbers of Canadians are joining the over-65 age bracket, new influenza vaccine formulations and strategies will be needed. The results of a recent randomized clinical trial demonstrated that a high-dose vaccine offers improved protection over the traditional dose vaccine.

Chief Medical Editor: Dr. Léna Coïc, Montréal, Quebec

Data collected at some 30 hospitals over four influenza seasons confirm the consistently high burden of disease in elderly Canadians. Of the more than 4000 cases assessed since 2009 by the Serious Outcomes Surveillance (SOS) network, two-thirds were over age 65 and approximately half were over age 75. Mortality during or within 30 days of hospitalization ranged from 8% to 11%. Influenza B, widely considered less common and severe in the elderly than in younger patients, is approximately as likely as influenza A to lead to elders’ hospitalization, admission to an intensive care unit, and death, reported Dr. Shelly McNeil, Professor of Medicine, Dalhousie University and Infectious Diseases Consultant, Queen Elizabeth II Health Sciences Centre, Halifax.

Influenza, Hospitalization and Frailty

The SOS Network data highlight that frailty is both a risk factor for, and a potentially long-lasting complication of, influenza. Frailty in the elderly population is defined as vulnerability or having a reduced capacity to tolerate health insults, stated Dr. Melissa Andrew, Assistant Professor of Geriatric Medicine, Dalhousie University, Halifax. The concept takes into account numerous factors including physical condition, illnesses, mobility, appetite, basic functioning in daily activities, cognition and mood. A high frailty score is more strongly predictive than age of negative outcomes including mortality, hospitalization, admission to a nursing home and development of dementia.

Hospitalization for influenza often engenders or worsens frailty through the addition of functional deficits or comorbidities. In some instances, the increased frailty or loss of functional abilities can lead to catastrophic disability. “The biggest risk factor for this type of disability is a hospital stay, and pneumonia and influenza are high on the list [of causes],” Dr. Andrew stressed. “These are illnesses we think of as having a short time horizon. You get the flu, it puts you down for a week or two, then you get back to where you were... But for older people, it’s particularly the case that they’re likely to be left with lasting deficits... We see often that people come in walking and leave needing assistance.”

Exercise, social integration and preventive health care are key to averting frailty, Dr. Andrew indicated. Improved uptake of immunization against influenza and pneumococcal disease has the potential to reduce the cascade of morbidity leading to disability and death. “Anything we can do to help our older people stay on the usual-aging and more robust health trajectories is going to be good for them,” she remarked. SOS Network data indicate that immunization against influenza prevents some 30% to 50% of hospitalizations, Dr. McNeil observed. She added, “We have some data to suggest that vaccinated people are less likely to have this accumulation of frailty when they are hospitalized.”

The impact of frailty should be considered when evaluating any vaccine’s effectiveness, Drs. McNeil and Andrew emphasized. Frail individuals are more likely to receive influenza vaccine, leading to an indication bias. “So if you don’t take frailty into account…you may well underestimate the vaccine effectiveness,” stated Dr. Andrew. Conversely, ensuring adjustment for frailty increases the point estimate for a vaccine’s effectiveness by about 5%, Dr. McNeil added.

Aging Immune System

Older adults’ high risk for influenza and relatively low response to current vaccines are brought about by immune senescence – that is, weakened host defences and cell-mediated and humoral immunity, Dr. Andrew reminded delegates. A concept known as “inflammaging” also plays a role. Aging is often associated with a systemic pro-inflammatory state “that’s low-grade and asymptomatic but impacts peoples’ responses to other stressors,” she indicated. With age, humans depend increasingly on the innate rather than the adaptive immune system [similar to infants], she added. “Early in life you’ll have a benefit from having more pro-inflammatory agents around. That may help you survive to get to older age. However, if you still have that [systemic activity at a greater age], it can lead to this inflammaging paradigm which can, conversely, lead you to age less successfully [with] increased susceptibility to infectious diseases.” Similarly, she added, while vaccines work primarily by stimulating the adaptive immune system and TH1 responses, “older people actually have less of what the vaccines need to work.”

Adjuvanted Vaccines

Standard trivalent inactivated influenza vaccines (TIV) are about 60% effective in preventing laboratory-confirmed disease, noted Dr. Allison McGeer, Professor of Laboratory Medicine and Pathobiology and Public Health Sciences, University of Toronto. Although their effectiveness does decline with patient age, “they prevent many deaths and a lot of illness every year and they are cost-effective so they are enormously valuable,” she commented.

Certain new vaccine formulations are aimed at overcoming immune senescence, she indicated. In one randomized controlled clinical trial (McElhaney JE et al. Lancet Infect Dis 2013), ambulatory elderly patients who received the ASO3-adjuvanted vaccine rather than the TIV were 12% less likely to develop influenza; however, this result was not statistically significant. A vaccine adjuvanted with MF59 has been evaluated only in observational studies. In a Canadian setting, patients who received the adjuvanted vaccine compared with a TIV had an odds ratio of acquiring laboratory-confirmed influenza of 0.37 (Van Buynder PG et al. Vaccine 2013). Italian researchers evaluating the vaccine’s impact on hospitalizations determined that it performed better than a TIV when adjustments were made for age, underlying illness and functional status (Mannino S et al. Am J Epidemiol 2012).

High-Dose Vaccine

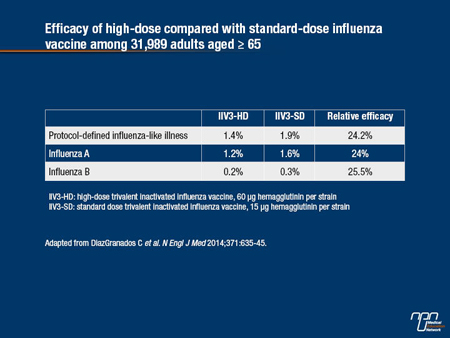

In a recent randomized, double-blind clinical trial involving more than 30,000 elderly adults (DiazGranados C et al. N Engl J Med 2014), a high-dose trivalent vaccine (60 μg of hemagglutinin per strain compared with the standard 15 μg) led to a significant 24% decrease in protocol-defined influenza (1.9% incidence on standard dose vs. 1.4% in high-dose recipients). The participants were slightly more likely to report injection-related pain with the high-dose injection; the 36% vs. 24% difference was primarily accounted for by minor pain. Erythema and swelling were also somewhat more frequent in the high-dose group. Systemic reactions were not significantly different between the groups. Overall, these differences did not alter the vaccine’s acceptability, Dr. McGeer remarked.

According to a recent report, giving the high-dose vaccine to US seniors would be more costly up-front than TIV and cost approximately the same as a quadrivalent vaccine. Compared with these vaccines, the high-dose option would prevent nearly 196,000 and 170,000 more cases of influenza, respectively. Further, it would prevent approximately 22,000 more hospitalizations and 5000 more deaths than either traditional vaccine (Chit et al. Vaccine 2014). Proportional cost-effectiveness is likely in Canada, although similar studies have yet to be done, according to Dr. McGeer.

Targeting the Elderly

Given their vulnerability to influenza and complications, including frailty and disability, it is important to continue to target the elderly for flu vaccines. Immunization rates in this population are still only about 50%, suggesting additional success with both existing vaccines and newer options is possible. Development of completely novel vaccines should also be supported, Dr. McGeer stated.

Table.