Reports

Iron Chelation Associated with Improved Survival in Diverse Hematologic Disorders

This report is based on medical evidence presented at sanctioned medical congress, from peer reviewed literature or opinion provided by a qualified healthcare practitioner. The consumption of the information contained within this report is intended for qualified Canadian healthcare practitioners only.

MEDICAL FRONTIERS - 53rd Annual Meeting & Exposition of the American Society of Hematology

San Diego, California / December 10-13, 2011

San Diego - New data presented during the 2011 ASH meeting have strengthened the evidence that iron chelation improves survival in patients with diseases involving dysfunctional red blood cells (RBCs). The data are particularly strong for myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS), but studies conducted in other hematological disorders, such as thalassemia, also expand evidence that iron chelation has important implications for outcome. Most major guidelines recommend monitoring ferritin levels in MDS patients and other groups that receive frequent RBC transfusions, but the new data also support an aggressive approach. Iron chelation is not a substitute for potentially curative treatments such as stem cell transplant when appropriate. However, the growing evidence that iron chelation increases survival and improves quality of life is rendering this treatment a standard in an array of hematologic disorders.

Chief Medical Editor: Dr. Léna Coïc, Montréal, Quebec

In patients requiring blood transfusions, which contain approximately 250 mg of iron/unit, iron overload develops quickly. Toxic iron levels can damage the heart, the skeleton and the liver. In those requiring chronic blood transfusions—including patients with myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) or other hematopoietic disorders, or those with thalassemia or sickle cell disease—iron stores must be reduced to prevent complications. With an established role in many of these disorders, iron chelation has been simplified with the development of oral therapies.

Indices of Improved Survival

The association of improved survival with iron chelation has altered the sense of urgency in providing therapy. “Iron overload in transfusion-dependent patients with chronic anemia has been associated with cardiac, hepatic and endocrine damage as well as reduced survival in some forms of cancer,” confirmed Dr. Roger Lyons, Cancer Care Centers of South Texas, San Antonio. “We know that transfusion dependence is associated with poorer clinical outcomes, including survival, in MDS, but that data we are seeing now suggesting iron chelation can improve overall survival demonstrate that the complications of transfusion dependence are reversible.”

The new data include those presented by Dr. Lyons in a 600-patient registry of lower-risk MDS patients from 107 participating centres in the US. Patients classified as lower risk by World Health Organization (WHO) and/or International Prognostic Scoring System (IPSS) have been stratified into 3 groups: non-chelated; chelated for <6 months; or chelated for =6 months. Follow-up data are now available for 24 months of a planned 5-year non-interventional registry. The median age of approximately 75 years and the male:female ratio of approximately 1.3:1 do not differ significantly between the 3 groups.

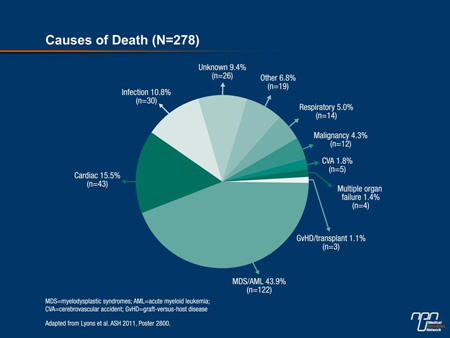

“Patients in the non-chelated, chelated [<6 months] and chelated for at least 6 months groups survived 52.2, 99.3 and 104.4 months, respectively. The difference between each chelated group and the non-chelated group was highly statistically significant [P<0.0001],” Dr. Lyons reported. Although the numbers were too small to compare differences in cause of death, nearly 45% of the deaths were due to MDS or to acute myeloid leukemia (AML) (Figure 1). It is notable that the percentage of patients who progressed to AML was higher in the non-chelated group (8.9%) relative to the chelated group (4.6%) and those chelated =6 months (5.2%), although the differences did not reach statistical significance.

“The trend toward lower AML transformation in the chelation groups is consistent with previous reports of reduced leukemia-free survival in iron overload patients,” Dr. Lyons observed.

Figure 1.

At baseline in this registry, 29.1% were receiving iron chelation; 25.2% were receiving the oral agent deferasirox. The remaining patients were receiving deferoxamine, which is administered by injection. Over the course of follow-up, those on chelation increased to 37%. It is notable that serum ferritin levels were similar in the 3 groups even though the median number of transfusions administered over 4-week intervals was approximately 2.1 units among those receiving chelation and 1.5 units for those who were not chelated.

In the follow-up to date, there have been no significant differences in the rate of hepatic or endocrinologic complications, but cardiac conditions have trended higher in the non-chelated group when compared to those on chelation for =6 months (46% vs. 39.8%; P=0.167). Dr. Lyons told delegates, “It is expected that the ongoing follow-up of this registry will provide further data on differences in outcomes between chelated and non-chelated patients.”

Improved Survival in Lower IPSS Risk Patients

In Canada, a retrospective review was conducted on outcome in relation to iron chelation in 182 patients with lower-risk MDS confirmed by bone marrow biopsy and IPSS score. The median age in this population was 70 and 60% were male. Although 75% of patients in this study received RBC transfusions, only 21% received iron chelation therapy. The median duration of the follow-up was just over 2 years, while the median duration of iron chelation therapy in those who received this treatment was 10.5 months.

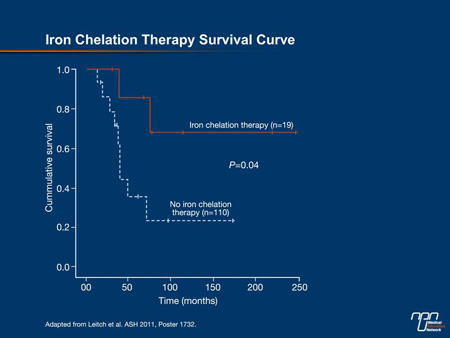

In this study, which divided the MDS population into those with refractory anemia and ring sideroblasts (RARS) and those without RARS, the benefit of iron chelation was concentrated in those without RARS. In this group, the 5-year survival was 91.7% in those who did receive iron chelation therapy vs. 39.2% in those who did not (P=0.04) (Figure 2). In those with RARS, the difference did not reach significance (76.3% vs. 72.4%).

“These results suggest an association between receiving iron chelation therapy and survival in lower IPSS risk patients in keeping with prior analyses. However, the association between iron chelation therapy and overall survival appears to be stronger in non-RARS patients,” reported Dr. Heather Leitch, St. Paul’s Hospital, University of British Columbia, Vancouver. Nevertheless, she cautioned against drawing firm conclusions, noting that follow-up may not be sufficient to capture a long-term survival benefit from iron chelation in those with RARS. Dr. Leitch advocated a prospective, randomized trial in order to provide evidence-based support for the growing use of this treatment.

The same types of benefits from iron chelation therapy are likely to accrue in all patients who are transfusion-dependent because of the same principles of rapid rises in iron levels.

Figure 2.

Time to Response and to Transfusion Independence

Here at ASH, Dr. Daniela Cilloni, University of Turin, Orbassano, Italy, discussed another multicentre retrospective study, this one conducted at 6 participating treatment centres in Italy; 105 patients with a variety of hematologic diagnoses were included. Although most had MDS (75 patients), there were 16 patients with primary myelofibrosis, 8 patients with aplastic anemia, 4 patients with chronic myelomonocytic leukemia and 2 patients with AML. Of the 98 patients on iron chelation, 68 were taking deferasirox and 30 were taking deferoxamine. At the time of starting iron chelation therapy, the median number of RBC units transfused was 30. The primary end point of interest was response to iron chelation therapy, including transfusion independence.

“Hematologic improvement, such as a reduction in the need for RBC transfusions, was common, demonstrating that iron chelation provides a significant degree of erythroid responses. About 20% of patients in this series became transfusion-independent,” reported Dr. Cilloni. She noted that 7 out of the 18 patients who became transfusion-independent were able to stop iron chelation therapy, and 4 of these have maintained their response a median of 12 months after discontinuation.

However, there were differences in the rate of response and the overall likelihood of response when oral deferasirox was compared to injectable deferoxamine. For example, the median time to response was 3 months for deferasirox and 6 months for deferoxamine (P=0.001). In addition, 12 of those on deferasirox vs. 5 of those on deferoxamine achieved transfusion independence (P=0.0003). Significantly more patients on deferasirox achieved a hemoglobin increase of >1.5 mg/dL than on deferoxamine.

”It is unclear why the response rates were both higher and faster with deferasirox, but the consistency of these results suggests that there may be some difference in their molecular mechanisms,” Dr. Cilloni stated.

End-organ Benefits

In thalassemia, the benefits of iron chelation appear to be transfusion independence. In presenting the results of the phase II THALASSA study, Dr. Ali T. Taher, American University, Beirut, Lebanon, reported that patients frequently develop iron overload with this condition because of increased intestinal iron absorption. Iron overload in non-transfusion-dependent patients with thalassemia is associated with serious complications to several organs, including the liver, as these patients age. The THALASSA study is the first prospective trial to test the benefits of iron chelation in this population.

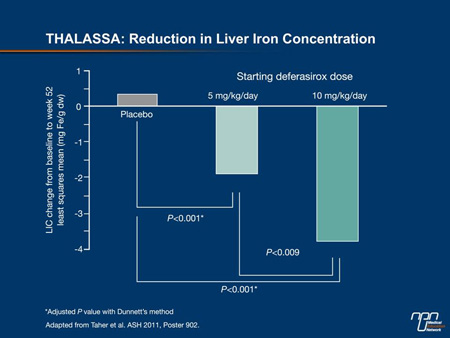

In this study, 166 patients with beta-thalassemia intermedia (95 patients), alpha-thalassemia (22 patients) or hemoglobin E-beta thalassemia (49 patients) were randomized to 1 of 4 arms: deferasirox 5 mg/kg/day or matching placebo; or deferasirox 10 mg/kg/day or matching placebo. Dose escalations of up to 20 mg/kg/day were permitted in patients with high iron overload levels. The primary objective was to compare liver iron concentrations (LIC) after 1 year of treatment, but other objectives, including change in serum ferritin and safety, were also evaluated.

Compared to the placebo groups, in which LIC increased 0.38 mg Fe/g dw at the end of 52 weeks, the concentration fell 1.95 mg Fe/g dw on the 5 mg/kg dose (P=0.001 vs. placebo) and 3.80 mg Fe/g dw on the 10 mg/kg dose (P<0.001) (Figure 3). The proportion of patients who had at least a 30% reduction in LIC over the 52 weeks was 1.8% on placebo, 25.5% on the 5 mg/kg dose and 49.1% on the 10 mg/kg dose. These changes are consistent with the changes in serum ferritin, which increased by 115 ng/mL on placebo but was reduced by 121 ng/mL (P<0.001 vs. placebo) on the 5 mg/kg dose and by 222 ng/mL (P<0.001) on the 10 mg/kg dose.

Figure 3.

“The reductions in LIC were highly statistically significant, and these were achieved with an overall frequency of adverse events that was comparable to placebo,” Dr. Taher told delegates. Based on the risks of persistently high levels of LIC in non-transfusion-dependent thalassemia patients, Dr. Taher concluded that chelation therapy should be considered in all thalassemia patients of this type when their LIC exceeds 5 mg Fe/g dw.

The same conclusion was reached in another study presented at ASH regarding the risk posed by iron overload to the heart. In this study, 41 patients with thalassemia major were treated with deferasirox at a mean dose of 26 mg/kg/day for a median of 12 months. Data presented by Dr. Elena Cassinerio, Ospedale Maggiore Policlinico, Milan, Italy, showed a statistically significant improvement of myocardial T2* from 27.4 ms at baseline to 29.8 ms at end of study (P=0.004). Also significant was improvement in left ventricular ejection fraction, which rose from 63.6% to 65.5% (P=0.013), suggesting improved cardiac function.

“When we analyzed those with higher baseline T2 iron loads [10-20 ms] with those with lower [>20 ms], there was greater improvement in ventricular volumes among those with higher loads, but there was still significant benefit in those with lower loads,” Dr. Cassinerio reported. Although the studies evaluating improvements in iron overload in end organs did not have sufficient follow-up to evaluate the effect on outcomes, it is reasonable to expect that these improvements would have important implications for subsequent events. In vulnerable patients experiencing diminishing cardiac function, these would be expected to include improvement in survival.

In patients with aplastic anemia, new data suggest deferasirox may also improve hematologic parameters as it reduces iron overload. Previously reported in EPIC, it was associated with a significant reduction in serum ferritin levels. In a new post-hoc analysis of 72 of the 116 patients who had hematologic parameters measured at baseline and at the end of treatment, 35 (48.6%) had at least a partial hematologic response. However, when the focus was on the 24 patients who received deferasirox without immunosuppressive therapy, the response was 66.7%; all became transfusion-independent.

“Similar to MDS patients, alongside a reduction in iron overload, deferasirox may improve hematologic parameters in aplastic anemia patients,” reported Dr. Jong-Wook Lee, St. Mary’s Hospital, Seoul, South Korea. Based on this and other data, he suggested that a “decrease in iron load could play a role in inducing a hematologic response.”

Summary

Iron chelation therapy can be applied to modify the course of hematologic diseases, including in patients with hematopoietic disorders who require frequent blood transfusions. The data associating iron chelation with improvements in survival of prospectively collected data from a US registry of 600 lower-risk MDS patients are compelling and changing practice at many centres. The ability to offer iron chelation with oral therapy has facilitated this movement. Importantly, iron chelation with current therapies is well tolerated with a low risk of adverse events.

Questions and Answers

The following question-and-answer session was conducted with Dr. Heather Leitch, St. Paul’s Hospital, University of British Columbia, Vancouver.

Q: The large body of data supporting iron chelation in a variety of diseases, including MDS, seems very compelling. Why is this not standard care?

A: Iron chelation is being used at many institutions routinely, but the obstacle has been the lack of multicentre, randomized trials. There has been accumulating evidence that iron chelation is beneficial, and one could make this assumption just on the known risks of iron overload in MDS and other diseases where this is a problem, but the prospective studies should be done and are now being planned.

Q: Iron overload is hardly a new challenge. Why have the trials never been carried out?

A: One problem was that the treatments were cumbersome. For years, the treatment for iron overload was phlebotomy, and this is not only problematic but contraindicated in patients with hematopoietic disorders. The introduction of deferoxamine was a step forward but this is an injectable agent, and this treatment is also difficult for patients who require treatment long-term. I think the introduction of oral agents has substantially increased interest in this field. Several have been developed. [Only deferasirox is available in Canada. Deferiprone was introduced in the US as of October 13, 2011.]

Q: You looked at survival in your study, which is certainly a compelling end point.

A: Our data are consistent with several published studies, so we think the data are pretty strong, but retrospective analyses have important limitations, and we have to conclude that these results are really hypothesis-generating. However, I will say that we are now using [oral] iron chelation therapy for lower-risk MDS patients at our institution, and many others are also doing so in advance of the prospective data that are needed for firm conclusions to be drawn.