Reports

LHRH Agonism vs. LHRH Antagonism: Cardiovascular Disease Difference Now Documented in Large Pooled Analysis

This report is based on medical evidence presented at sanctioned medical congress, from peer reviewed literature or opinion provided by a qualified healthcare practitioner. The consumption of the information contained within this report is intended for qualified Canadian healthcare practitioners only.

PHYSICIAN PERSPECTIVE - Viewpoint based on presentations from the ECCO-17 - 38th ESMO Multidisciplinary Congress

Amsterdam, The Netherlands / September 27-October 1, 2013

Guest Editor:

Dr. Pierre I. Karakiewicz, MD

Urologic Oncologist,

Associate Professor and Senior Outcomes Research Scientist

Director, Cancer Prognostics and Health Outcomes Unit

University of Montreal Health Centre

Montreal, Quebec

Introduction

Luteinizing hormone-release hormone (LHRH) agonists have a long history as first-line agents for the treatment of androgen-sensitive prostate cancer (PC). By acting on LHRH receptors in the pituitary, LHRH agonists—also called gonadotrophin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonists—stimulate release of luteinizing hormone (LH). As a result, there is an initial surge or flare in testosterone until such time that LHRH receptors become desensitized to overstimulation and testosterone is subsequently reduced to castrate levels. In contrast, LHRH antagonists directly bind to the same LHRH receptors in the pituitary, causing an immediate blockade of endogenous LHRH actions. Testosterone is immediately suppressed without any initial surge in gonadotrophin or testosterone levels on either the first or subsequent doses, an effect that more closely mimics the effect of surgical castration. Follicle-stimulating hormone is also suppressed to a greater degree with LHRH antagonists at approximately 90% from baseline compared with approximately 50% with LHRH agonists. As a third-generation LHRH antagonist, degarelix is probably the most closely scrutinized drug among first-line agents for PC and it has been widely compared to LHRH agonists. Most recently, a pooled analysis of 6 clinical trials comparing it to LHRH agonists has shown that cardiovascular disease (CVD) events were lower in the overall cohort receiving the LHRH antagonist and especially lower among men who had CVD prior to study enrolment compared with those receiving a LHRH agonist. Findings should help shape decisions when evaluating which drug class is the more suitable form of androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) in men requiring ADT after surgical or radiation failure.

ADT and CVD

A number of reports have linked ADT to an increased risk of both diabetes and CVD including an observational study in veterans with PC reported by Keating et al. (JNCI 2010;102(1):39-46). A total of 37,443 men who had been diagnosed with local or regional PC were included in the analysis. Of this cohort, 39% had received ADT. Analysis showed that treatment with GnRH agonists was associated with a statistically significantly increased risk of diabetes at a rate of 159.4 events per 1000 person-years vs. 87.5 events per 1000 person-years for those on no ADT—almost a 72% excess risk of diabetes for GnRH agonist recipients.

The same analysis also showed a higher incidence of coronary heart disease, myocardial infarction (MI), sudden cardiac death and stroke for GnRH agonist users vs. non-users. In a more recent study [Eur Urol 2013. Published ahead of print Feb. 12, 2013] Jespersen et al. analyzed a national cohort of 31,571 patients with incident PC registered in the Danish Cancer Registry. Of these, 29% received medical endocrine therapy (not specified) while 2060 or 7% of the overall cohort were orchiectomized. Results showed that men treated with medical endocrine therapy had about a 30% increased risk of MI and about a 20% increased risk of stroke (adjusted HR of 1.31 and 1.19, respectively) compared with non-ADT users.

In contrast to earlier studies, Danish investigators found no increased risk for either MI or stroke following orchiectomy. Thus, medical ADT does carry an increased risk of CVD in general—a point the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) as well as Canadian regulatory officials acknowledged when they placed warnings about an increased CVD risk on LHRH agonists. During the 2013 European Cancer Congress, Dr. Bertrand Tombal, Professor of Urology, Universite Catholique de Louvain, Brussels, Belgium presented results from a pooled analysis of 6 randomized phase 3 trials carried out following approval of degarelix by the FDA. Of the 6 trials included in the pooled analysis, 3 trials lasted 3 months, while the other 3 lasted between 7 and 12 months. In all, 1686 patients received 1 year of ADT while 642 patients received 3 to 7 months of ADT.

A total of 1491 patients received the LHRH antagonist while 837 others received either goserelin or leuprolide. Groups were well matched for baseline characteristics as well as history of CVD. “Patients were hormone-naïve and were candidates for LHRH agonist or antagonist therapy,” as Dr. Tombal observed, “and most were presenting with biochemical failure after either radiation therapy or radical prostatectomy.” The majority also had a Gleason score of between 7 and 10. Approximately 20% had either metastatic disease or high PSA baseline values. Event analysis was based on death from any cause or occurrence of a serious CV event.

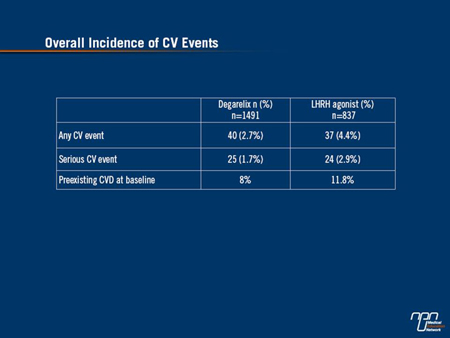

As Dr. Tombal reported, the risk of CVD events was significantly lower in LHRH antagonist recipients than their LHRH agonist counterparts. Specifically, the overall incidence of any CV event was 2.7% for degarelix recipients vs. 4.4% for those who received a LHRH agonist. Only 1.7% of the LHRH antagonist recipients experienced a serious CV event compared to 2.9% of LHRH agonist recipients (Table 1).

Table 1.

A serious CV event was one that was considered life-threatening or that required hospitalization, as Dr. Tombal observed.

Established Baseline CVD

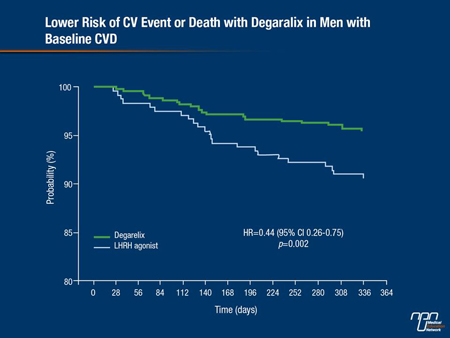

Confining the CV analysis to men who had established baseline CVD, investigators also found there was a 56% lower risk of having a CV event or death among men treated with the LHRH antagonist compared with LHRH agonist groups (P=0.002) at the end of one year (Figure 1). Adjusting for variables affecting CVD risk, there was still a greater than 50% reduced risk for men with a CVD history at baseline who received the antagonist compared with the agonist group (P=0.004) as Dr. Tombal also observed.

Figure 1.

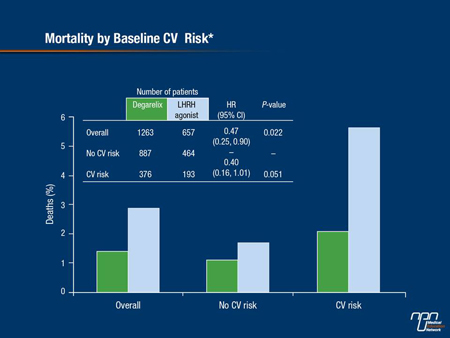

In contrast, there was no difference in CV event risk or mortality among men who had no CVD at baseline between either comparator arms (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

PSA Progression or Death

Not surprisingly, the same pooled analysis showed that the percentage of men who had evidence of PSA progression or who died over the 1-year follow-up was higher in patients with higher baseline PSAs (both >20 to 50 ng/mL and >50 ng/mL), Dr. Tombal continued. However, overall results were still in favor of the LHRH antagonist, particularly in men with a PSA >50 ng/mL at baseline, among whom 66% achieved PSA PFS status at 1 year compared with 54.7% of agonist recipients (P=0.0245 for PSA failure in favor of the LHRH antagonist group).

Broadening the analysis to include men with a baseline PSA >20 ng/mL, LHRH antagonist recipients were 26% more likely to achieve PSA PFS status at 1 year compared to active controls—a difference which was of borderline significance (P=0.051). In the overall cohort, 98.3% of men taking degarelix compared with 96.7% of men taking a LHRH agonist were alive at the end of the first year of treatment (P=0.0329).

Urinary Tract and Bone Health

Consistent with reports that indicate a substantial benefit from LHRH antagonism in terms of both a reduction in prostate volume and an improvement in urological symptoms, the pooled analysis showed that rates of urinary tract AEs were significantly lower with LHRH antagonist treatment (P<0.0001) while time to first urinary tract infection was significantly longer (P=0.001).

Interestingly, overall rates of joint-related symptoms were also lower in the degarelix group at 5.3% compared to 8.1% for the LHRH agonist group (P=0.0116). The overall probability of fracture at <1% was also lower in the LHRH antagonist group compared with 2% for the LHRH agonist group (P=0.0234). In men over the age of 70, fracture risk was 74% lower in the LHRH antagonist group as well (P=0.0137), and the incidence of muscle or bone pain was also lower for men receiving LHRH antagonist treatment (P=0.0822).

“Global adverse events (AEs) between the comparator arms were quite similar,” Dr. Tombal indicated. Injection site reactions were more common with the LHRH antagonist, likely because the drug is given as a double injection on first-time dosing, as he noted, concluding that:

“This analysis demonstrates that during the first year of treatment, men treated with degarelix had a reduced occurrence of disease-related side effects including urinary tract symptoms and fractures and we believe this is a substantial improvement for the treatment of hormone-naïve PC patients.”

Published On-line

In a pre-print, online published article of the same pooled analysis, Albertsen et al. (Eur Urol 2013, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2012.10.032) pointed out that for most men, a rise in serum PSA following radical surgery or radiation therapy is sufficient to trigger initiation of ADT. “As a consequence,” they write, “men now receive ADT for considerably longer periods of time, resulting in a greater recognition of the side effects associated with treatment.”

These side effects include not only the well-known effects of androgen deprivation but metabolic changes including lipid alterations that contribute to CV risk. In light of the new pooled analysis, Dr. Tombal suggested in an on-line presentation (http://www.europa-uomo.org/docs/eau2013/News_europauomo%20Tombal.pdf) that patients with a history of vascular disease should be considered for antagonist-based ADT given that degarelix essentially halved the risk of men having a CV event over one year compared with LHRH agonists.

If there is no history of CVD but the PSA is >20 ng/mL they again should be considered for antagonist therapy as the pooled analysis showed that men with a PSA >20 ng/mL had longer PSA PFS times than those on either of the 2 agonists.

Men with metastatic disease also had a longer PSA PFS and improvements in both bone pain and fewer skeletal fractures if they received degarelix; they too, could benefit from an antagonist-based ADT strategy. And men with baseline LUTS and a IPSS >12 could also benefit from an LHRH antagonist as the pooled analysis demonstrated there was better relief of LUTS in men receiving degarelix than for those receiving either leuprolide or goserelin.

Alternative Form of ADT

Previous experience using degarelix as an alternative form of ADT had already confirmed its efficacy in the treatment of early PC. The fact that its pharmacological profile differs from that of the LHRH agonists also invites comparisons between the two drug classes. In one of the more important of these comparator trials (CS21), investigators assessed the efficacy of degarelix vs. that of the LHRH agonist, leuprolide, for achieving and maintaining testosterone suppression over 1 year [BJU Int 2008;102:1531-38]. A total of 610 patients with PC were randomized to monthly leuprolide, 7.5 mg or to degarelix, 240 mg for 1 month followed by monthly maintenance doses of either 80 mg or 160 mg.

The primary end point was suppression of testosterone to ≤0.5 ng/mL between days 28 and 364. At one year, almost identical treatment responses were observed in all treatment arms at approximately 98% for both doses of the LHRH antagonist compared to approximately 96% in the LHRH agonist arm. However, as pointed out by Dr. Neal Shore, Medical Director, Carolina Urologic Research Center, Myrtle Beach, Florida (Ther Adv Urol 2013;5(1):11-24), the LHRH antagonist led to faster suppression of testosterone than leuprolide with no accompanying testosterone surge.

Indeed, 96% of patients had achieved castrate testosterone levels of ≤0.5 ng/mL by day 3 in both degarelix dosing groups. In contrast, no patients on leuprolide had achieved castrate testosterone levels at the same time point. A later review of the CS21 data by Tombal et al. [Eur Urol 2010;57:836-42] also indicated that the risk of PSA failure or death was 34% lower in the degarelix 240/80 mg group compared with the LHRH agonist group (P=0.005). As Dr. Shore pointed out, almost half of the CS21 cohort had advanced disease and PSA failure occurred mainly in this subgroup.

By day 28 of the trial, Tombal et al also noted that regardless of baseline disease stage, 59% of patients receiving degarelix had achieved a PSA <4 ng/mL compared with 34% of their leuprolide counterparts (P<0.0001). Study authors also note that there was an initial increase in PSA in patients with metastatic disease receiving leuprolide—an effect that was not seen with degarelix in the same patient group.

After 1 year in the CS21 trial, those randomized to either maintenance dose of degarelix continued on the same maintenance dose while those in the LHRH agonist arm were randomized to one of the 2 maintenance doses. After a median follow-up of 27.5 months, the risk of PSA progression in 1 year was more than halved in patients who crossed over from leuprolide to degarelix at the end of the CS21 trial.

Changes in PSA PFS rates from year 1 to year 2 of the study were not significant for patients who continued on the now-approved 240/80 mg maintenance regimen. As Dr. Shore observes, both the antagonist and the agonist were well tolerated in CS21 with a similar incidence of treatment-emergent AEs.

No allergic reactions were observed in men receiving the LHRH antagonist although injection-site reactions occurred significantly more frequently in the degarelix group compared to those receiving leuprolide (P<0.001).

As Dr. Shore also points out, the more rapid suppression of testosterone achieved with the use of the LHRH antagonist translates into more rapid PC-related symptom relief. The absence of flare with degarelix use is also important, he adds, as flare symptoms can be serious. Improvements in PSA PFS rates seen with degarelix in the CS21 trial compared with leuprolide as well as in those who crossed over from the agonist to the antagonist has important clinical implications. Firstly, the delay in PFS as reflected by PSA levels suggests that there will be a delay in progression to castrate- resistant disease in men receiving antagonist therapy. Delay in disease progression means that men should enjoy a longer interval during which they have minimal physical and psychological morbidities.

This is even true of patients with the highest PSA failure rates in the CS21 trial for whom the time to PSA failure or death was delayed by approximately 7 months— a clinically meaningful therapeutic effect seen with LHRH antagonism over the agonist alternative.

Summary

Prostate cancer is now the most common significant cancer among Canadian men, accounting for about one-quarter of all new cancer cases each year. In 2013, the Canadian Cancer Society estimated that approximately 23,600 men were diagnosed with PC while close to 4,000 men died from it. Looked at another way, 65 Canadian men, on average, are diagnosed with PC every day. Timely diagnosis and early intervention with the most effective form of ADT offers patients the best opportunity to stave off disease progression and improve survival without impairing quality of life over what can be many years of treatment. That it can be done more safely with the LHRH antagonists is simply an added advantage to their use.