Reports

New Insights in the Treatment of Atypical Hemolytic Uremic Syndrome

This report is based on medical evidence presented at sanctioned medical congress, from peer reviewed literature or opinion provided by a qualified healthcare practitioner. The consumption of the information contained within this report is intended for qualified Canadian healthcare practitioners only.

PRIORITY PRESS - Annual General Meeting of the Canadian Society of Nephrology

Montreal, Quebec / April 24-28, 2013

Montreal - Atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome (aHUS) is a rare condition caused by a genetic or acquired deficiency in the complement system. Its features include progressive and potentially fatal involvement of the kidneys and circulatory and CNS. Plasma exchange or infusion may be effective but a clinical response is not assured and adverse effects are relatively common. Studies presented here demonstrated the efficacy and safety of the monoclonal antibody eculizumab in reducing hematologic and clinical signs of aHUS and improving quality of life. Speakers also confirmed the need for additional exploration of the causes and mechanisms of aHUS.

Chief Medical Editor: Dr. Léna Coïc, Montréal, Quebec

Atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome (aHUS) is a rare condition often caused by one or more genetic deficiencies in the complement component of the immune system. The disorder produces unregulated activation of the alternative pathway; uncontrolled and chronic complement cascade activation leads to platelet activation, thrombosis, hemolysis and thrombotic microangiopathy (TMA). Effects include progressive and potentially fatal involvement of the kidneys, circulatory, gastrointestinal and central nervous systems (CNS). Other TMA include Shiga toxin Escherichia coli (STEC-HUS) and thrombotic thrombocytopenia, and should be included in the differential diagnosis.

“The outcome of aHUS is not good. A number of patients will end up in end stage renal disease [usually within three years] and our goal must be to save kidney function by proper treatment,” remarked Dr. Martin Bitzan, Director, Pediatric Nephrology, Montreal Children’s Hospital, Quebec. Within a year of diagnosis, more than 50% of patients with aHUS need dialysis, have irreversible renal damage or will die.

Although aHUS is often defined as a hematologic disease which strikes the kidney, it has a far greater impact, confirmed Dr. Christoph Licht, Associate Professor of Pediatrics and Nephrologist, Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, Ontario. “We have underappreciated in the past the systemic character of the disease. We have only in recent years appreciated and learned about extrarenal manifestations in the CNS and basically all other organ systems.”

Complement System Deficiencies

In patients with suspected aHUS, a causal diagnosis is ideal although a specific mutation is not always identifiable. Among patients with aHUS, about 1 in 3 has a mutation or antibody affecting Factor H of the complement system, explained

Dr. Bitzan. Deficiency of Factor I or membrane cofactor protein and other complement-activating or -regulating proteins may also be implicated. “Right now with optimal diagnostics it is possible to identify the complement inhibitor dysregulation in about 50% to 60% of patients with aHUS,” he added.

Treatment Options

Therapeutic plasma exchange or plasma infusion (PE/PI) have been the most widely recommended treatment for aHUS,

Dr. Bitzan indicated. However, plasma therapy can be technically problematic and, especially in children, is associated with adverse events such as allergic reactions, clotting or bleeding and viral infections following aggressive therapy or long-term exposure. “We are in the process of evaluating all patients who have been on treatment…and a high rate indeed had catheter and thrombosis problems and infection problems. And [PE] is disruptive for children who need long-term therapy,” observed Dr. Bitzan. Moreover, clinical response to PE/PI is not consistent. “Some patients respond well then stop, others continue responding for a longer period, and some never respond,” noted Dr. Licht.

Health Canada approved the humanized monoclonal antibody therapy eculizumab for the treatment of aHUS. Eculizumab binds to the C5 complement protein, blocking the generation of pro-inflammatory proteins (C5a and C5b-9). In this way, it inhibits the terminal complement system including the formation of the membrane attack complex.

As an effective therapy for aHUS, it appears to avoid the safety and tolerability issues identified with plasma therapy,

Dr. Licht stated. “The drug, as far as we know, has a low side effect profile and seems to be highly efficient. And with that, it’s really a breakthrough for patients with complement-mediated disease, especially aHUS.” He cautioned that so far, clinical data have been collected primarily in adolescents and adults. “We don’t have a lot of experience in children younger than 12 years of age treated for a long period.”

In initial studies, eculizumab was shown to inhibit the systematic and progressive TMA process, thereby preventing and even reversing organ damage. After one year of treatment, 95% of patients receiving eculizumab had experienced no TMA-related clinical events and had a 30% increase in glomerular filtration rate (GFR). The treatment also improved the patients’ quality of life.

Two-Year Data

In single arm, open-label extension studies presented here, Dr. Licht and colleagues examined the efficacy and safety of eculizumab treatment continued for 2 years in patients with aHUS. One study (poster 115) enrolled 17 patients with a median disease history of 9.7 months, evidence of renal damage and progressing TMA despite chronic PE/PI. Each received eculizumab 900 mg/wk for 4 weeks, 1200 mg the next week and 1200 mg every 2 weeks thereafter.

Among patients with low baseline platelet counts, 87% experienced normalization of platelet levels by 26 weeks and the majority (12/13) maintained this result for 2 years. Hematologic normalization was achieved in 76% of patients by week 26 and 85% at 1 year; this result was sustained at 2 years. TMA event-free status (12 consecutive weeks without a drop in platelets of >25% from baseline and no new plasma therapy or dialysis) was achieved and maintained at 2 years by 88% of individuals in the study. Improvements in estimated GFR (eGFR) and renal function were also observed.

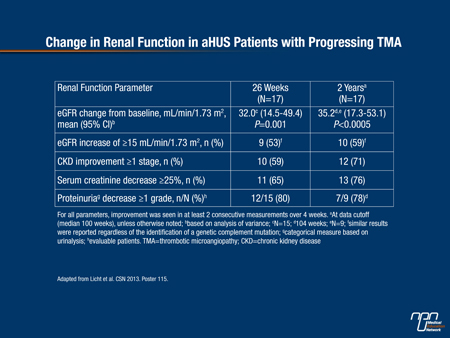

In the second trial (poster 116), the investigators reported that among 20 patients who had aHUS for a median duration of 48 months and associated chronic renal failure, 90% achieved hematologic normalization and 80% achieved TMA-event-free status at 26 weeks. The percentages were 90% and 95% respectively at 2 years. Ongoing eculizumab treatment also led to continued improvement in eGFR, chronic kidney disease stage, serum creatinine and proteinuria levels over the course of the study (Table 1).

Table 1.

In both trials, terminal complement inhibition occurred as quickly as 1 hour post-infusion and was sustained out to

2 years. The effect of eculizumab was similar among patients with various complement mutations. The medication was deemed safe and well tolerated; adverse event rates remained steady or declined as the study progressed.

Patients receiving long-term therapy with eculizumab reported an improved quality of life, as measured by EQ-50 score. The change was more striking than expected, Dr. Licht commented. “Even in patients who don’t have very obvious extrarenal symptoms, there is something you can summarize as a chronic fatigue issue…When they were treated with this drug, many spontaneously reported improved energy levels. And that is, in my mind, a very convincing argument for the systemic character of the disease and the efficacy of this treatment.”

Research Continues

Further studies of eculizumab will ideally help answer some outstanding clinical questions, such those related to optimal dosing, Dr. Licht stated. “Can we treat with less and be equally efficient? Or at the other extreme, since we have documented breakthroughs on treatment following the current standard dosing…when do we have to [increase] the dose to prevent those breakthroughs?”

According to the current understanding of aHUS, chronic, lifelong treatment is needed. “In this condition, be it genetic or autoimmune, the underlying cause doesn’t go away. You are just efficiently dealing with the consequences of the disease. Now with that, you have clearly a rationale for ongoing treatment,” Dr. Licht commented. However, it is conceivable that identification of specific genotypes or phenotypes may generate a risk spectrum that suggests more or less aggressive treatment.

The causes and mechanisms of aHUS also require substantial further exploration, Dr. Licht remarked. “We still [need] research to complete the genetic insight and to understand what’s going on at the molecular level.”