Reports

Centre Hospitalier Universitaire de Montréal

This report is based on medical evidence presented at sanctioned medical congress, from peer reviewed literature or opinion provided by a qualified healthcare practitioner. The consumption of the information contained within this report is intended for qualified Canadian healthcare practitioners only.

PHYSICIAN PERSPECTIVE - Get with the PROTOCOL - A Regional Perspective on the Evidence and Resulting Changes in ACS Protocol

April 2013

Reviewed and edited by:

André Kokis, MD, FRCPC, FACC

Cardiologist

Head of Interventional Cardiology

Centre Hospitalier Universitaire de Montréal

Associate Professor of medecine

Université de Montréal

Montreal, Quebec

Introduction

Antiplatelet therapy in the management of acute coronary syndromes (ACS) has recently been revised at the Centre Hospitalier Universitaire de Montréal (CHUM). The altered algorithm is designed to provide significant reductions in risk of major cardiovascular (CV) events by employing the newer antiplatelet agents compared to the previous standard of clopidogrel and ASA. The new algorithm specifies where prasugrel and ticagrelor should be employed to provide additional protection against major CV events. Guided by the large clinical trials that underlie the revised algorithm, the specific recommendations allow for the clinical gains from greater antiplatelet effect, including in some cases, a lower risk of death. They also balance benefit with an acceptably low risk of major or minor bleeding. Due to the fundamental importance of deactivating platelets to alter the natural history of evolving ACS events, optimal use of antiplatelet therapy should be considered an essential strategy for improving the prognosis of ACS. The new protocol is consistent with revisions in national guidelines.

Previous Standard: Need for Improvement

The dual antiplatelet strategy of clopidogrel and ASA in patients presenting with ACS has been a widely employed standard for more than 10 years. However, rates of cardiovascular (CV) events in acute coronary syndrome (ACS) populations remain substantial. In the landmark CURE study, 10% of those receiving clopidogrel plus ASA went on to a recurrent myocardial infarction (MI), a persistent arterial occlusion or died of a CV cause despite the 20% reduction with the combination relative to ASA alone.1 This study was performed in patients with non-ST elevation MI (NSTEMI). In the CLARITY-TIMI 28 trial, conducted in patients with ST elevation MI (STEMI), the residual risk of death, stroke or MI was 9% in the group receiving clopidogrel plus ASA despite a 31% reduction in MI relative to ASA alone.2

Since those studies established this dual antiplatelet combination as a standard in ACS, 2 large ACS trials have proven that more effective antiplatelet therapy will further reduce CV risk. One trial tested ticagrelor in an all-comer population of ACS patients.3 The other study tested prasugrel in ACS patients scheduled for a percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI).4 Data from these trials provide an opportunity to improve outcomes over the previous clopidogrel plus ASA standard.

In the TRITON TIMI-38 study, 13,608 ACS patients scheduled for PCI were randomized. In the experimental arm, patients received a loading dose of prasugrel (60 mg) followed by maintenance prasugrel (10 mg daily). The comparator arm received a loading dose of clopidogrel (300 mg) followed by maintenance clopidogrel (75 mg daily). Both groups received ASA. Approximately 25% of the ACS events were STEMI and the remaining NSTEMI.

Relative to clopidogrel, prasugrel reduced the risk of the composite end point of death from CV cause, MI or stroke by 19% (HR 0.81; P<0.001). The risk of major bleeding on prasugrel was increased by 32% (HR 1.32; P=0.03) relative to clopidogrel. There was no difference in mortality. The authors concluded that the greater protection against ischemic events must be weighed against an increased risk of bleeding, but post-hoc analyses provided guidance for candidate selection.

In the PLATO trial, all individuals admitted to hospital with ACS were randomized regardless of planned procedure or pre-hospital antiplatelet treatment. The experimental arm received a loading dose of ticagrelor (180 mg) followed by maintenance ticagrelor (90 mg twice daily). The comparator arm received a loading dose of clopidogrel (300 or 600 mg) followed by maintenance clopidogrel (75 mg daily). Both groups received ASA. Approximately 37% of the 18,624 patients randomized had STEMI and the remaining had NSTEMI.

Relative to clopidogrel, ticagrelor reduced by 16% the relative risk of the composite end point of death from vascular causes, MI or stroke (HR 0.84; P<0.001). The difference in total major bleeding (11.6% vs. 11.2%; P=0.43) did not reach statistical significance. However, bleeding rates were not equal in some of the subcategories. In particular, ticagrelor was associated with a higher rate of major bleeding not related to coronary artery bypass grafting (non-CABG) than prasugrel (4.5% vs. 3.8%; P=0.03). Differences in life-threatening or fatal bleeding were not significant between agents. Unique to antiplatelet trials, ticagrelor was associated with a 22% reduction (HR 0.78; nominal P<0.001) in all-cause mortality (death from vascular causes 21%, HR 0.79; nominal P<0.001).

New Data Translated into Clinical Practice

The revised treatment algorithms for antiplatelet therapy in ACS patients are designed to capture the opportunity to improve outcome based on the PLATO and TRITON-TIMI 38 trials. While all ACS patients should be initiated on ASA immediately, the second antiplatelet agent is defined by the diagnosis, the planned strategies for intervention and specific patient characteristics. Several large organizations have altered ACS antiplatelet guidelines on the basis of the PLATO and TRITON-TIMI 38 trials, but algorithms at the regional or hospital level are appropriate because of differences in ACS care.

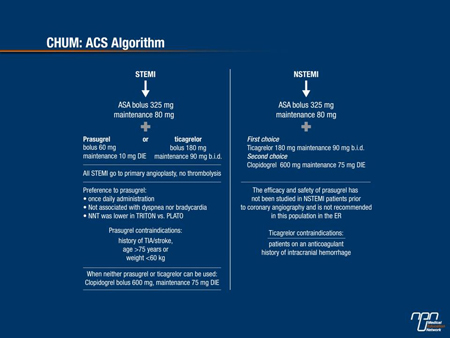

At regional centres, including the CHUM, the data generated by the PLATO and TRITON-TIMI 38 trials can be applied directly. In NSTEMI patients, ticagrelor is now the dominant partner in a dual antiplatelet strategy with ASA with important exceptions. These exceptions include patients on an anticoagulant or who have had a prior intracranial hemorrhage (Figure 1). In those not candidate for ticagrelor, clopidogrel remains the preferred partner with ASA. In those initiated on clopidogrel who are candidates for ticagrelor according to the algorithm, the therapy should be switched.

Figure 1.

In STEMI patients scheduled for PCI, prasugrel has been found more effective than clopidogrel in a dual antiplatelet strategy with ASA, but the benefit-to-risk ratio varied across subpopulations in the registration trial, producing some important exceptions. As a result, clopidogrel remains the preferred partner with ASA in individuals who have received anticoagulants or prior treatment with a fibrinolytic agent as well as in those over the age of 75 years, those who weigh <60 kg and those with a prior transient ischemic attack or stroke. In these individuals, the evidence suggests that the greater risk of major bleeding negates the clinical benefit provided by the relative reduction in CV events. The new guidelines have placed both prasugrel and ticagrelor on top of clopidogrel for STEMI, but prasugrel is preferred. Ticagrelor is kept on the protocol for those STEMI patients who have contraindications to prasugrel but not to ticagrelor.

Figure 2.

Relevance of New Algorithm to Regional Centres

The objective evidence that newer antiplatelet therapies can improve the outcome in ACS patients informs but does not dictate adjustments in patient care. Due to substantial regional disparities in the care of ACS driven largely by variability in resources, such as the proximity of rapid response teams and differences in transfer intervals to catheterization laboratories, treatment guidelines must be adjusted for relevance to current practice. At regional centres, treatment algorithms must be adjusted for these variables. The same opportunities to improve outcome with more effective antiplatelet regimens should not be overlooked. Current practice at regional facilities is relevant to community hospitals whether or not the transfer of patients is common.

The new guidelines at the CHUM include several assumptions that may or may not be relevant to nearby community centres. For example, the improvement in outcome associated with prasugrel in STEMI patients scheduled for PCI is based on the availability of PCI. However, the revised algorithm is evidence-based and does specifically outline areas in which clopidogrel plus ASA should no longer be considered the standard.

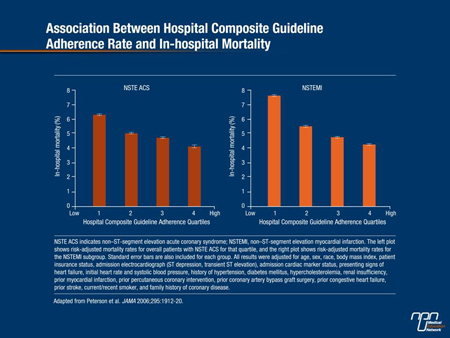

There are compelling data to conclude that implementation of more modern strategies for appropriate candidates will improve ACS outcomes including a reduction in mortality. The implementation and adherence to treatment guidelines in the management of ACS has been associated with statistically significant improvements in outcome. In an observational analysis that included 350 academic and non-academic centres, a stepwise 10% reduction in in-hospital mortality rates was associated with each 10% increase in adherence to evidence-based guidelines.5

Conclusion

The first-line antiplatelet strategies in ACS patients have been revised. The newer agents ticagrelor and prasugrel provide an important opportunity to improve outcome relative to clopidogrel when any of these agents is combined with ASA. In NSTEMI patients, the advantage of ticagrelor over clopidogrel in appropriately selected patients includes a mortality reduction. The guidelines developed by the CHUM were designed specifically to identify these opportunities in a readily applied algorithm.

Question & Answers

Q: What is your perspective on the benefit-to-risk ratio that the newer antiplatelet agents offer within the revised algorithm for reducing the risk of thrombosis within an acceptable rate of bleeding?

A: Both TRITON-TIMI 38 and PLATO were randomized trials and both showed that the 2 new molecules are superior to clopidogrel. Despite a slightly increased bleeding risk, the benefit still outweighs the risk.

Q: The studies that led to changes in the guidelines compared therapies in different populations. What insights can you offer on why it was important to prove superiority of prasugrel or ticagrelor over clopidogrel in different ACS groups (STEMI, NSTEMI, unstable angina, etc)?

A: Before it can be prescribed, a medication needs to have been studied in the targeted population as the data cannot be extrapolated. This means that antiplatelets must have been studied not only in ACS in general, but in all 3 types of ACS, i.e. STEMI, NSTEMI and unstable angina. Considering that neither compound has been studied in stable atherosclerotic coronary disease and elective angioplasty, clopidogrel remains the mainstay of treatment in these settings.

Q: What is your point of view on the possible side effects associated with the newer agents vs. the opportunity to improve outcomes?

A: Any treatment has adverse events, but these become more acceptable when hard end points such as infarction, stroke or death are reduced. Bleeding can be managed mainly by proper patient selection, which means that patients with contraindications or at high risk of bleeding must be excluded. The other adverse events are insignificant in my opinion.

Q: The algorithm introduces some decision points not previously required when all patients were treated with clopidogrel plus ASA. What action needs to be taken to improve outcomes?

A: Yes, decisions need to be made with this new algorithm. All physicians, including cardiologists, ER physicians, residents, internists, etc., need to be made aware. It is important that new algorithms be based on guidelines, which are themselves evidence-based. Education is the key to guidelines implementation.

References

1. Yusuf et al. Effects of clopidogrel in addition to aspirin in patients with acute coronary syndromes without ST-segment elevation. N Engl J Med 2001;345(7):494-502.

2. Sabatine et al. Addition of clopidogrel to aspirin and fibrinolytic therapy for myocardial infarction with ST-segment elevation. N Engl J Med 2005;352(12):1179-89.

3. Wallentin et al. Ticagrelor versus clopidogrel in patients with acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med 2009;361(11):1045-57.

4. Wiviott et al. Prasugrel versus clopidogrel in patients with acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med 2007;357(20):

2001-15.

5. Peterson et al. Association between hospital process performance and outcomes among patients with acute coronary syndromes. JAMA 2006;295(16):1912-20.