Reports

“Long-COVID is Not New” Long-term Sequelae Common in Flu, Especially in Older Adults, Say Influenza Researchers

This report is based on medical evidence presented at sanctioned medical congress, from peer reviewed literature or opinion provided by a qualified healthcare practitioner. The consumption of the information contained within this report is intended for qualified Canadian healthcare practitioners only.

MEDICAL FRONTIERS - AMMI Canada–CACMID Annual Conference 2022

Vancouver, BC / April 5-8, 2022

Vancouver – Influenza started to make a comeback worldwide and in Canada towards the end of 2021, emerging from the 2020–2021 pandemic lockdowns. A symposium at the recent AMMI Canada-CACMID annual conference updated participants on flu in older adults, with insights and data that have emerged ‘while flu was away’. Non-respiratory sequelae of COVID such as MI, strokes and ‘long-COVID’ are not a new phenomenon in viral infections, speakers reminded the audience: long-term life-limiting sequelae have always been a concern with influenza, particularly in older adults. The audience was also updated on the current landscape of influenza vaccines for older adults and new analyses comparing their effectiveness.

Chief Medical Editor: Dr. Léna Coïc, Montréal, Quebec

“We talk about long COVID…and sequelae like fatigue and organ dysfunction as if it’s a new thing. But it’s not possible that COVID is the first illness that’s causing these long-term sequelae; obviously… other viruses have done this before,” said Dr. Melissa Andrew, Professor, Medicine (Geriatrics) and Community Health and Epidemiology, Dalhousie University, Nova Scotia.

Dr. Andrew made her remarks in an interview following a virtual symposium at the AMMI Canada-CACMID Annual Conference held in Vancouver on April 5–8, 2022. The accredited symposium, co-developed with Seqirus – who had no input into the content – was entitled Our Older Adults: How can we Better Protect Them from Influenza and its Devastating Effects?

During her talk Dr. Andrew reminded her audience that we’ve known for 20 years that influenza has many long-term complications, especially in older adults. “There’s a great body of work that’s been happening over many years to show that it’s not just about the acute respiratory infection,” Dr. Andrew said. “It can trigger events such as cardiovascular events and strokes and certainly can contribute to the risk of falls and fractures.”

A paper by Kwong and colleagues published in the New England Journal of Medicine in 2018 found that in the first 7 days after a laboratory-confirmed influenza infection there was a six-times increased risk of acute myocardial infarction compared to 1 year before and 1 year after the infection (N=364; incidence rate ratio [IRR] 6.05; CI 3.86 to 9.50).1 The study was funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research.

A team of clinicians from Providence, Rhode Island, and Harvard Medical School in 2018 found that, in their hospitals over 9 years, up to two additional admissions for influenza-like illness (ILI) in a given week was significantly associated with a 1% increase in hip-fracture hospitalization risk (N=9,237; overall IRR 1.13; CI 1.08 to 1.17).2

Dr. Andrew said that if 100 older adults were hospitalized for influenza – whatever their baseline frailty and level of function – 12 would die and 20 would have functional decline. In half of these (nine), the functional decline would be mild; the remaining half (11 people) would have a catastrophic functional decline and three would end up in a nursing home.

Said Dr. Andrew, “These are all excellent reasons to prevent influenza in the first place.”

Many studies show an association between influenza vaccination in older patients and a reduction in long-term sequelae. For example, a cohort study by Chen et al. using data from the Taiwan Longitudinal Health Insurance Database between 1997 and 2008 found that influenza vaccination in > 55 years old patients with chronic kidney disease reduced the risk of hospitalization for acute coronary syndrome (ACS) by 65% (N=4,406; HR 0.35; p<0.001).3 There was a dose-response: the risk of ACS hospitalization declined significantly with the number of vaccinations the patient received over the time period, from an adjusted HR of 0.62 (CI 0.52–0.81) for one vaccination to 0.13 (CI 0.09–0.19) for four or more flu vaccinations.

“Influenza is a major driver of complications and poor outcomes that we really want to think about,” concluded Dr. Andrew, “particularly for the older population.”

How Effective are Flu Vaccines in Older Patients?

Dr. Andrew told her audience that immune responses change with age, but it’s not simply a question of reduced immune response: “What immune-senescence means [is that] it’s not necessarily a reduction in immune responses, but rather that they’re dysregulated.” This means, among other things, Dr. Andrew explained in an interview, that “antibody response doesn’t fully capture the benefit of vaccines, particularly for older people.”

Furthermore, Dr. Andrew said, flu vaccines are more effective in people aged 65+ than the data suggest because of the impact of frailty on effectiveness data. “Someone who is frail is just barely managing to keep their day-to-day functional independence and if they get that same [infection] they take longer to recover and may or may not get back their independence,” she explained.

Dr. Andrew cited an analysis she published in 2017, showing that influenza vaccination in the 2011–12 season was 45% effective at preventing hospitalization in patients > 65 years. When adjusted for frailty the vaccine was 58% effective.4 There was a steady decrease in vaccine effectiveness across frailty groups.

Dr. Andrew added that “it’s super important” to view vaccine effectiveness data through the lens of frailty. “If we don’t adjust [for frailty] we will tend to underestimate and really not understand the full benefit of vaccination,” she said.

“We shouldn’t have messaging that says vaccines are less effective for older people as a whole, because really most older people are not frail – only about a quarter are,” Dr. Andrew concluded. “But we also need to target our vaccine development and programs and coverage at the people who are in greatest need of protection, like the frail people.”

Influenza is Back

At the symposium, Dr. Allison McGeer, Professor, Laboratory Medicine and Pathology, Dalla Lana School of Public Health, University of Toronto, reviewed the current status of influenza globally and in Canada.

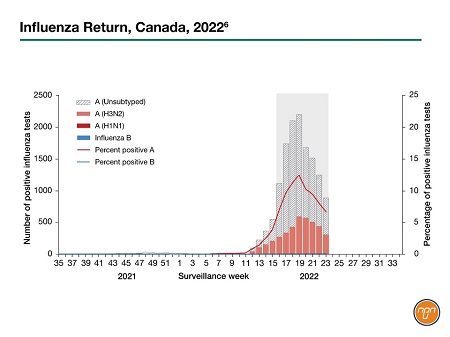

She reminded her audience of the dramatic “chopping off” of the 2019–2020 flu season due largely to public health measures as the world went into pandemic lockdown. World Health Organization surveillance in the North Hemisphere5 shows that flu started to make a comeback towards the end of 2021, Dr. McGeer said, with a “fairly typical start to the season in terms of timing” but much smaller numbers than usual. “The same thing is happening on a smaller scale in Canada”, Dr. McGeer said, with the number of flu isolates at the time of the conference, April 2022, “dramatically lower than usual” (data at the time of going to press presented in Figure 16).

Figure 1.

Vaccines for Older Adults

Dr. McGeer summarized the “enhanced” seasonal flu vaccines authorized for older adults in Canada: one cell-derived vaccine (Flucelvax Quad); one high-dose product (Fluzone High Dose); one recombinant (Supemtek); and one MF-59 adjuvanted vaccine (Fluad). Although all are available, there is wide variation in public funding across provinces. Only Ontario covers the adjuvanted vaccine, for example, and none of the provinces pays for the recombinant vaccine.

The most recent recommendation from the National Advisory Committee on Immunization (NACI) on vaccines for older adults came out in 2019. NACI stated that “Any of the available influenza vaccines should be used” as there was insufficient evidence to make comparative recommendations.

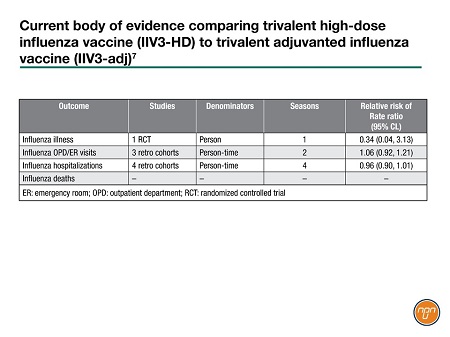

Dr. McGeer said that NACI is currently working on an updated recommendation. Meantime, Dr. McGeer presented a systematic review published in February by the Centers for Disease Control (CDC),7 using similar methodology to that of NACI. The CDC drew on 49 studies, only about half of which had infection outcomes, so “It’s still not a really large literature”, commented Dr. McGeer.

Dr. McGeer said that there was “a consistent reduction in adverse outcomes across the studies”. Eight studies compared high-dose and adjuvanted vaccines (Table 1). The retrospective data showed no difference between the two vaccines; the single RCT was small and did not show a statistically significant difference. “So really, we still need more data,” to make clinical recommendations on high-dose versus adjuvanted vaccines, concluded Dr. McGeer. See Q&A (page 4) for more commentary from Dr. McGeer.

Table 1.

Influenza in the COVID Era

Dr. McGeer said that she expects to see some significant changes in flu vaccines for older adults in the future. “The pandemic has disrupted so many things and post-this Fall, [we’ll see] a lot of disruption in what we’re giving people for influenza vaccines in the years after this.”

Meantime, Dr. Andrew said that we should not forget about flu during the ongoing COVID pandemic. “We’re very focused, and rightly so, on COVID. We just want to make sure that as we’re recommending that our older patients get COVID vaccines and boosters we need to remember to incorporate influenza,” she concluded.

Conclusions

The COVID-19 pandemic changed many things in the world of influenza clinical science. On the one hand, it shone light on the dramatic benefits of public-health measures in curbing seasonal influenza and the need to consider long-term sequelae as well as acute infection when weighing the clinical benefits of vaccination, especially in older adults. COVID-related vaccine technology may change the influenza vaccine landscape. Conversely, flu experts caution that influenza, particularly in older adults, should not be forgotten in the face of the ongoing pandemic and clinicians should continue to protect their patients’ lives and future independence through appropriate flu vaccination.

Questions and Answers

Questions and answers on influenza, vaccines and older adults. Following her presentation at the AMMI Canada-CACMID Annual Conference 2022, MedNet invited commentary from Dr. Allison McGeer, Professor, Laboratory Medicine and Pathology, Dalla Lana School of Public Health, University of Toronto.

Q: During your presentation, you described how the 2019–2020 flu season was ‘chopped off’ when the COVID lockdown began. Why did COVID affect flu numbers?

Dr. McGeer: When we first saw it, I thought maybe it was because we weren’t testing for flu anymore, because we were all just focused on COVID. But it is very dramatic and it occurred globally…There’s still room to argue that it might be about COVID activity, but it’s much more likely to be associated with health measures: I think there’s no question now that this effect was related to lockdown for COVID.

Q: Why was this a surprise to public health experts?

Dr. McGeer: Modeling pre COVID told us that in a [flu] pandemic we were not going to be able to affect the course of the pandemic to a substantial degree with public health measures… We've now learned what happens to seasonal flu with masking and social distancing and lockdowns…Which of those things actually work to reduce influenza? It’s an open question.

Q: How might we use this information going forward?

Dr. McGeer: I think that, short term, we'll probably be much more willing to use routine masking in congregate living settings than we have been; the ‘allergy’ to masking does not exist so much in long-term care settings. My guess would be that we will at least try routine masking [in this setting] during respiratory outbreaks. I don't think there’s an appetite at the moment to have routine masking to try to prevent outbreaks.

Q: In her presentation, Dr. Melissa Andrew stressed that ‘long COVID’ is not unique: flu also has serious long-term sequelae, especially in older adults. In your opinion, will the focus on ‘long COVID’ have knock-on benefits when it comes convincing patients to get vaccinated for flu?

Dr. McGeer: I'm not certain how we can translate that because people have been saying this for the last 20 years. It’s the problem with flu – it’s so ‘ordinary’ that people have trouble taking it seriously. [And] we aren't making the diagnosis of long COVID in older adults very much. I think that's because we expect when older adults get affected some of them don't get better. And we just kind-of live with that.

Q: Now that influenza is back, what do you want your colleagues to know about flu in older adults?

Dr. McGeer: Firstly, that there remains a gap in influenza prevention in older adults, that we will be able to respond to, likely with the next generation of vaccines: there's going to be this huge change in the vaccine landscape in the next three or four years. There’s good reason to hope that that will result in our ability to do much better at preventing influenza in older adults. [We’re] already on that pathway, right? Already, we have better influenza vaccines for older adults. Second, if we want this program to be successful, if we want to be able to prevent influenza in older adults, we need to find a different mechanism for paying for vaccines… the [current] structure of how we pay for vaccines in Canada means that we cannot effectively implement publicly funded vaccination programs for older adults.

References:

1. Kwong JC, Schwartz KL, Campitelli MA, et al. Acute myocardial infarction after laboratory-confirmed influenza infection. N Engl J Med 2018; 378:345–353.

2. McConeghy KW, Lee Y, Zullo AR, et al. Influenza illness and hip fracture hospitalizations in nursing home residents: Are they related? J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2018; 73:1638–1642.

3. Chen C, Kao P, Wu M, et al. Influenza vaccination is associated with lower risk of acute coronary syndrome in elderly patients with chronic kidney disease. Medicine 2016; 95:1–9.

4. Andrew MK, Shinde V, Ye L, et al. The importance of frailty in the assessment of influenza vaccine effectiveness against influenza-related hospitalization in elderly people. J Infect Dis 2017; 216:405–414.

5. https://apps.who.int/flumart/Default?Hemisphere=Northern&ReportNo=5

6. https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/publications/diseases-conditions/fluwatch/2021-2022/week-23-june-5-june-1-2022.html.

7. McGeer A. Data presented at AMMI Canada-CACMID Annual Conference 2022. https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/114834